When I think back to Italia ’90, the first images that come to mind are not just of goals, celebrations or tears, but of Panini stickers. I can still see the blue pages of that World Cup album, where the great nations each enjoyed their double spread, while the so-called “lesser” teams were squeezed together, their players sharing stickers as if they were somehow less important.

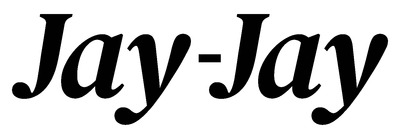

This brings me to sticker 173. The left half of it taken up by Joseph-Antoine Bell, the other half by Thomas N’Kono. Two goalkeepers, two faces of a team I knew little about at the time. For me they were just exotic names from Cameroon, neighbours on a sticker page. Little did I know that they were two of the finest goalkeepers Africa would ever produce – and protagonists in one of the most fascinating rivalries the position has ever known.

The Golden Era of the Indomitable Lions

Through the 1980s, Cameroon rose from curiosity to continental benchmark. With the iconic Roger Milla up front, they became kings of Africa and the continent’s most consistent World Cup representatives.

But within that golden generation, the greatest rivalry was not between striker and defender, but between two men who wore the same gloves. The simultaneous emergence of Thomas N’Kono and Joseph-Antoine Bell was almost miraculous. In a country of just seven million people in the mid-1970s, to produce two world-class goalkeepers at the same time defied belief.

They were both influenced by a remarkable coaching lineage. Former French and Yugoslav greats like Dominique Colonna and Vladimir Beara worked in Cameroon, instilling modern methods and bold ideas. Beara, one of the greatest goalkeepers of his own era, was the first to call both N’Kono and Bell into the national fold. He taught them to be mobile, proactive, aggressive – a break from the stereotype of static African keepers. Both men were also from the Bassa ethnic group, a minority that somehow produced an extraordinary number of Cameroon’s sporting legends, from Roger Milla to Samuel Eto’o.

It was in this fertile environment that the duel between N’Kono and Bell took root.

The Beginnings in Africa

Born in 1956 in Dizangue, Thomas N’Kono’s story is the stuff of folklore. He walked to training as a teenager while working in a shoe factory, before joining Éclair Douala in the second division. By 18 he was at Canon Yaoundé, Cameroon’s dominant club, and within a year he was captain. They called him The Black Spider, echoing Lev Yashin, because of his long limbs and his seemingly supernatural saves.

With Canon, he won five league titles and two African Champions Cups. His performance in the 1978 final against Guinea’s Hafia FC – a string of miraculous saves to hold a 0-0 draw – became legendary. In 1979 he was crowned African Footballer of the Year, the first goalkeeper to receive the honour. He would win it again in 1982.

Two years older, Joseph-Antoine Bell was born in 1954 in Mouandé. His path could not have been more different. At 17 he was wrongly imprisoned for 18 months on a charge of public indecency. Released, he viewed football as secondary to his academic ambitions – his father was a teacher, and Bell wanted to become an engineer.

But football pulled him back. With Union Douala he won two Cameroonian titles and the 1979 African Champions Cup. In 1980 he left for Ivory Coast with Africa Sports, winning the league. Then Egypt with Arab Contractors, where he lifted both the league and the African Cup Winners’ Cup.

Spain ’82: Debut on the World Stage

When the 1982 World Cup began, both players were still playing their football in Africa. N’Kono, 25 at the time, was the first choice, while Bell, 27, was in the squad but unused.

Cameroon were outsiders, debutants. Yet they left unbeaten, drawing all three games and conceding just once – against Italy, the eventual champions. N’Kono was extraordinary. His acrobatic one-handed save from Peru’s Barbadillo, flicking the ball behind his back before hurling it downfield, made him a cult hero. Journalists ranked him the second-best goalkeeper of the tournament, behind only Rinat Dasaev, but ahead of Zoff, Shilton and Schumacher.

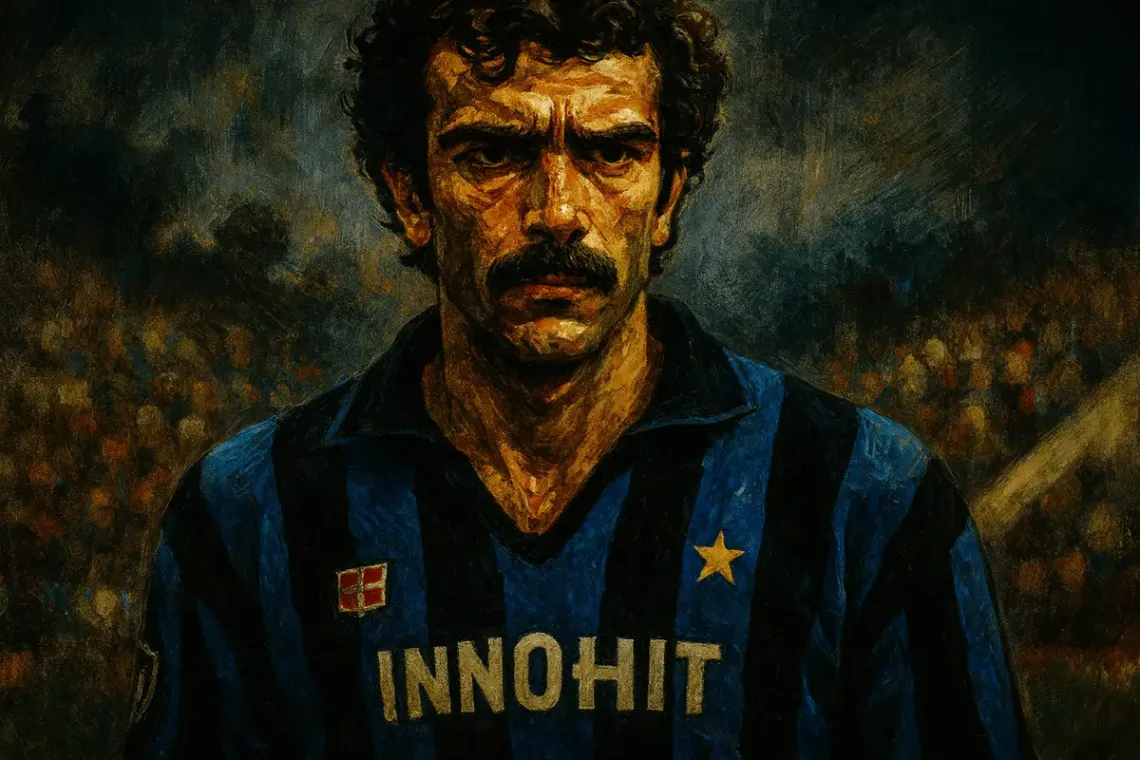

His reward was a move to Espanyol Barcelona. For nearly a decade he was their rock, playing 303 games and twice voted La Liga’s best foreign player. In 1988 he led Espanyol to the UEFA Cup final, beating Sacchi’s Milan and Trapattoni’s Inter along the way. They won the first leg 3-0 against Bayer Leverkusen, only to lose the second 0-3 and fall on penalties. N’Kono called it “the greatest disappointment of my career”.

But by then his legend was secure: the first African goalkeeper to be a consistent starter in Europe, a pioneer who destroyed stereotypes with every save.

Sharing the Shirt: AFCON ’84 – ’88

In the national team, the pendulum swung with ruthless frequency. At AFCON 1984, N’Kono began as number one but left after two games due to club obligations; Bell stepped in and never gave the shirt back, keeping consecutive clean sheets as Cameroon won their first continental title.

Soon after, in 1985 and already aged 30, Bell finally landed in Europe with Marseille. There he showed his class: brave with the ball at his feet, elegant in catching crosses where others punched, and master of the psychological duel on penalties. In the 1986 French Cup final he famously hid his hands behind his back, offering no clue to Bordeaux’s Reinders, before springing the right way to save.

In that same year, coach Claude Le Roy feared the chemistry of two alpha goalkeepers and decided to take only one of them to the AFCON in Egypt. He left Bell out, fearing two stars could destabilise the camp. Bell lashed out publicly, calling Le Roy incompetent. Cameroon still reached the final, losing on penalties to hosts Egypt.

In 1988, Le Roy relented. Bell was recalled and was named goalkeeper of the tournament as Cameroon won again. N’Kono accepted his place on the bench with quiet dignity. The rivalry had edges, but it also had results.

Italia ’90: Five Hours to Immortality

After three successful seasons at Marseille, Bell left the club in 1988 after publicly criticising Bernard Tapie’s running of the club. After one season with Toulon, he joined Bordeaux in 1989.

When he returned to the Vélodrome, now playing for Bordeaux, he was subjected to a grotesque display: bananas hurled at him from the stands. Bell turned the moment into a platform, denouncing xenophobia and calling out the hypocrisy of French football.

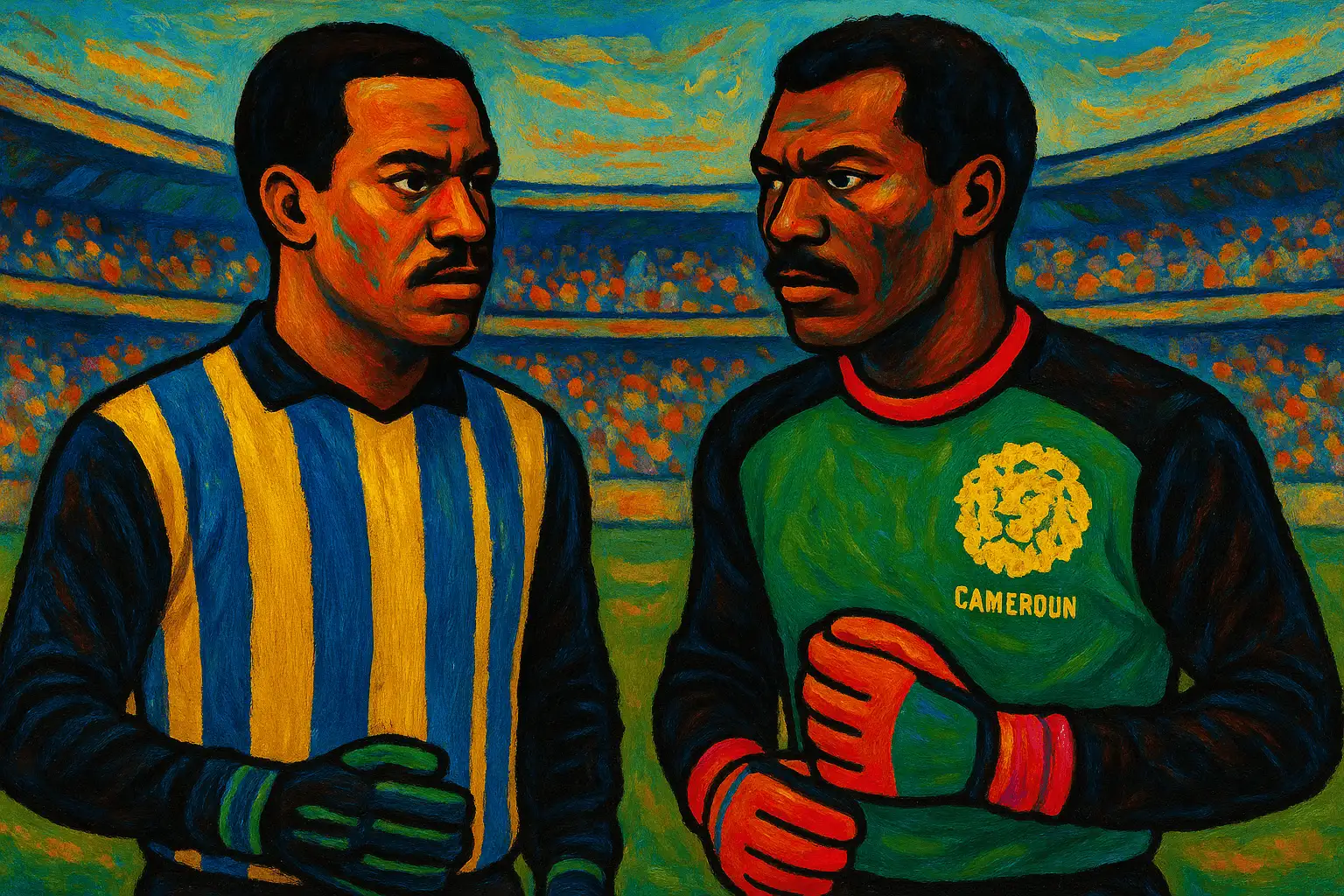

And so we arrive at the 1990 World Cup in Italy. Bell, 35, travelled as presumptive starter after a superb Ligue 1 season; N’Kono, 33, would be the reserve. Then politics roared in. On the eve of the opener against Argentina, Bell – the players’ loudest voice in a dispute over unpaid bonuses – gave a blunt interview about Cameroon’s chaotic preparation. Five hours before kick-off in Milan, the federation overruled the coach: Bell out, N’Kono in. N’Kono later admitted he initially refused to play, distrusting the process, before agreeing out of duty.

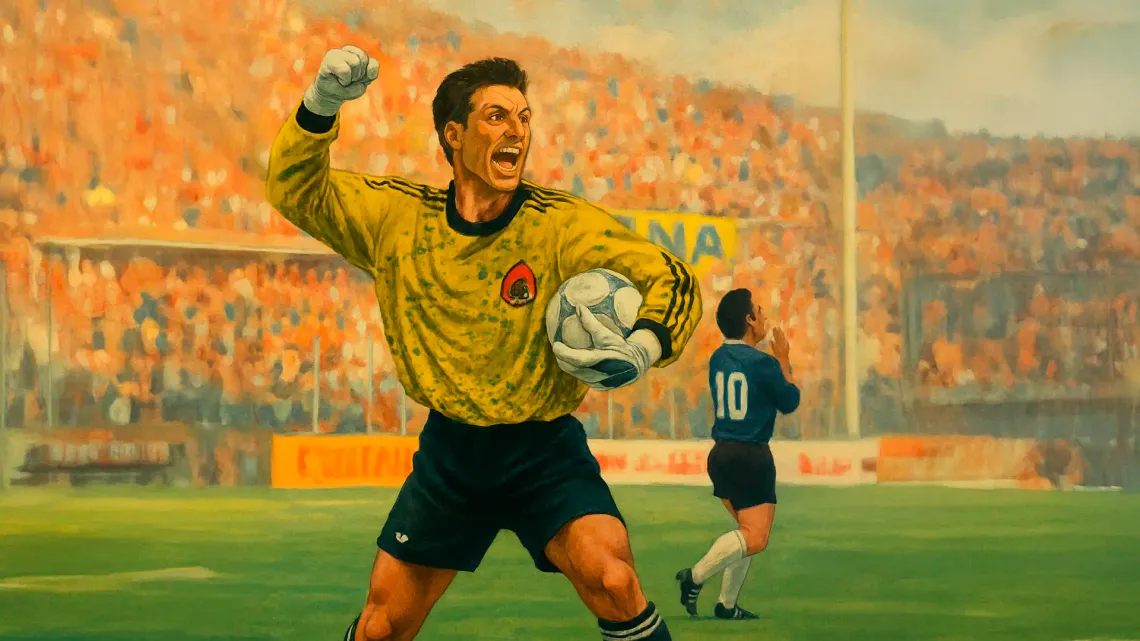

What followed is football scripture: nine-man Cameroon beat Maradona’s reigning champions Argentina 1-0. The heroics of Omam-Biyik and Kana-Biyik are remembered, but N’Kono was immense. He repelled shots from Balbo, Burruchaga, Caniggia and Maradona himself. His towering presence embodied the Indomitable Lions.

Cameroon went on to beat Hagi’s Romania, then shocked Valderrama’s and Higuita’s Colombia in the round of 16 with Roger Milla - recalled from semi-retirement – dancing timelessly by the corner flag. Only in the quarter-final, against England, did they fall – and even then, only in extra-time. It was the first time an African team reached the last eight of a World Cup.

For N’Kono it was immortality; for Bell, devastation – a tournament watched in tracksuit, his reputation somehow both burnished and bruised by events off the pitch.

USA ’94: The Last Act

By 1994 the years had piled up: Bell was 39 and playing his last-ever season at Saint-Étienne; N’Kono, 37, was finishing his 14-year spell in Spain and would move that summer to Bolívar La Paz, where he would play three last seasons before retiring.

Henri Michel started with Bell, but the campaign was undermined by old arguments over money and selection. There were reports of attempted interference – even that officials wanted N’Kono restored mid-tournament before the squad pushed for Bell to keep the gloves.

A draw with Sweden was followed by heavy defeat to Brazil and a 6-1 collapse to Russia as Oleg Salenko famously scored five. Back home, anger turned ugly: Bell’s house in Douala was set alight by enraged fans. Football can be savage to its servants; the rivalry’s epilogue deserved better. The golden era was over, and with it the epic duel between two extraordinary keepers.

Legacies Beyond the Gloves

This was never just stylistic contrast; it was ideology. Bell was charismatic, outspoken, and political. He spoke in complete paragraphs, on and off the game – about bonuses, about governance, about how Cameroon played. He could be abrasive, but he insisted professionalism was a kind of love. N’Kono, quiet and stoic, framed things in saves, not sentences.

Around them, team-mates and journalists cast the pair as opposites: Bell the cerebral sweeper who pushed the line high, N’Kono the acrobatic sentinel who preferred the defence tucked in. Two valid creeds, two massive careers.

But N’Kono didn’t just inspire a generation; he altered the future of one prodigy. A 12-year-old Gianluigi Buffon watched him in 1990 and switched from midfield to goalkeeping, later naming his first son Louis Thomas in homage. After retiring, N’Kono coached at Espanyol, shaping Carlos Kameni and exporting the Cameroonian school of goalkeeping. He also lived through one of African football’s strangest headlines: arrested and handcuffed by riot police at AFCON 2002 in Mali after accusations of “black magic” before a semi-final – an indignity that said more about the environment than the man.

Bell, meanwhile, remained a voice of conscience. He worked as a radio analyst, ran for the presidency of the Cameroonian FA, and in 2012 was made chief of his native Mouandé. He became an enduring symbol of integrity and resistance, always outspoken against corruption and prejudice.

Verdict: Who Was the Greatest?

The debate remains unresolved.

The IFFHS and CAF named Bell Africa’s best goalkeeper of the 20th century. N’Kono, however, twice won African Footballer of the Year, something Bell never achieved.

N’Kono was the shot-stopper supreme: reflexes like a gymnast, dominance in the air, spectacular saves. Bell was cerebral: a reader of the game, almost a sweeper-keeper before his time, commanding the back line with intelligence.

Bell won two Africa Cups as starter. N’Kono shone on the world stage in 1982 and 1990. Bell’s club career spanned Marseille, Toulon and Bordeaux. N’Kono became a legend at Espanyol.

Who was greater? Perhaps the wrong question. Like Messi and Ronaldo, their rivalry pushed each other to higher levels. They shattered the stereotype that black goalkeepers could not be trusted, proving instead that African keepers could be world-class leaders.

Sticker 173

And so I return to my old Panini album. Little did I know that those two Cameroonian goalkeepers crammed onto a single small sticker were in fact giants of the game.

Whether you preferred N’Kono’s acrobatics or Bell’s authority, the truth is simple: football itself was the winner. They elevated each other, they elevated their nation, and they elevated the game.

Subscribe to our newsletter and get our news in your inbox

Member discussion