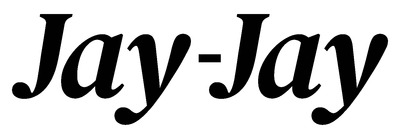

It’s impossible not to be struck by a character like Taribo West. Part of Nigeria’s golden generation - alongside Okocha, Kanu, Finidi and Babayaro - he also lined up beside Ronaldo at Inter Milan - a club as turbulent as it was talented, featuring stars like Iván Zamorano and Youri Djorkaeff. Yet beyond the trophies and the talent, what stayed with us was his look: the neon‑green braids, the flash of a grey front tooth, and the uncompromising, no‑nonsense defending that defined him.

And if that wasn’t enough, Taribo West was a free agent in Championship Manager 01/02 - freshly released from Derby County, armed with outrageous stats: 20 in aggression, strength and determination; 19 in stamina and bravery; 18 in balance and work rate.

What digital manager wouldn’t dream of signing a defender like that? He was a must-buy.

For those of us who lived our footballing dreams through keyboards and tactics screens, certain players became more than just names and numbers. We forged relationships with them - through miracle comebacks and last-gasp collapses, through heroic cup runs and the kind of soul-crushing defeats that left keyboards in pieces.

And that connection, however fictional at first, inevitably transferred to real life. Taribo West became one of those icons - part memory, part myth.

Officially, he was 27 in that season. But whispers had long swirled around his age. Not a couple of years off. Twelve. That would mean he was really 39 - and still playing elite football in Europe’s top leagues. Could that possibly be true?

Time to rewind the tape and revisit the life and career of one of African football’s most fascinating enigmas.

Port Harcourt beginnings

Taribo West was born-according to official records-on 26 March 1974, in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. His early years were marked by poverty, chaos, and the threat of criminal life. He ran with gangs-“bad boys,” as he called them-and helped his mother sell akara - a popular food - on the streets.

Like so many african kids, football was the escape route. It offered not just hope, but identity.

His first spiritual instincts also took shape during this period, and they would later define everything about him-his playing, his rituals, even his hair. He rose through Nigerian clubs Obanta United, Sharks, Enugu Rangers and Julius Berger, before catching the eye of European scouts.

Guy Roux’s Golden Generation

In 1993, supposedly aged 19, Taribo West signed for AJ Auxerre - a small-town club in the heart of Burgundy with an outsized reputation for producing talent. At the helm was Guy Roux, a legendary figure in French football who had built a dynasty on scouting intuition, discipline, and faith in young players-particularly from Africa.

Auxerre had long been a stepping stone for future stars, but between 1993 and 1997, it became something more. These were the club’s golden years, and West arrived just as the magic began to peak.

He settled into a defence anchored by the experienced Franck Silvestre, and during the 1995-96 season, was joined by Laurent Blanc, who spent one sublime campaign at the club before departing for Barcelona. West wasn’t just filling gaps; he was evolving into a rock-solid centre-back-still raw in moments, but brutally effective and increasingly dependable.

That same season, Auxerre achieved the unthinkable, winning both the Ligue 1 title and the Coupe de France, completing a historic domestic double. It remains the only time the club has ever been crowned champions of France.

They did it not with superstars, but with cohesion, grit, and a core of brilliant players who would go on to shine elsewhere. Lionel Charbonnier stood tall in goal; Corentin Martins and Sabri Lamouchi pulled the strings in midfield; Bernard Diomède added pace and flair out wide; and the goals came from the deadly feet of Stéphane Guivarc’h and Lilian Laslandes.

West played 28 league games that season, forming the backbone of a defence that conceded just 34 goals in 38 matches. He wasn’t flashy-at least not yet-but he was essential. Under Roux, he matured tactically, learned when to hold the line and when to step out, and began to impose himself not just physically, but psychologically. There was already something unshakeable about him.

By the time he left for Inter Milan in the summer of 1997, Taribo West had played over 80 matches for Auxerre, won two national cups, one league title, and been part of the club’s most legendary side. His story was still unfolding, but the foundations had been laid-in France, in Auxerre, in a team that defied history and logic to become champions.

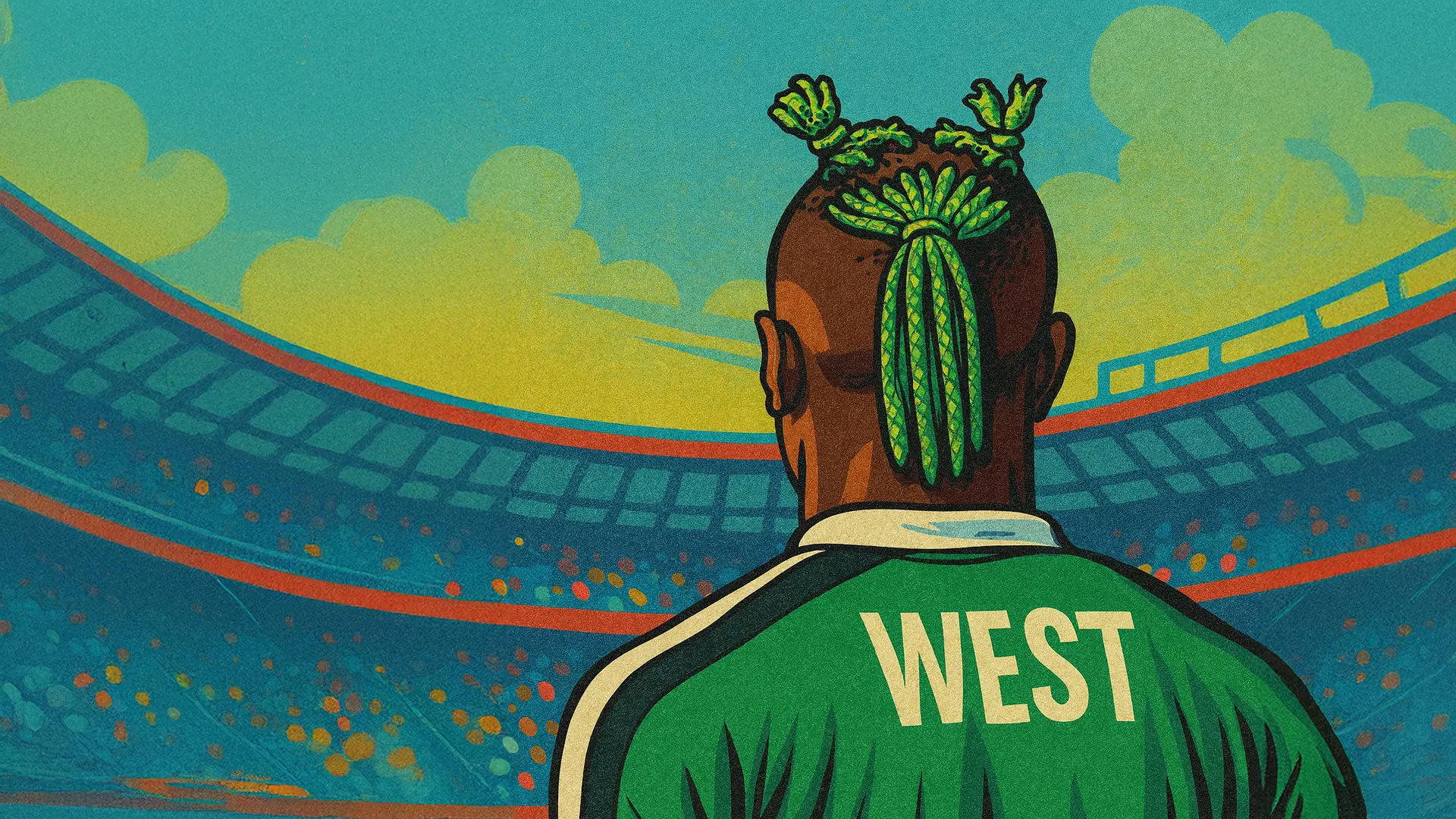

The Atlanta ’96 Miracle

By the summer of 1996, Taribo West was making a name for himself in France - but it was in the United States that his legend was etched in gold.

The Olympic Games in Atlanta produced one of football’s most romantic stories: Nigeria’s men’s team defied all odds to become the first African nation to win Olympic gold, stunning the world with fearless, joyous, attacking football.

The squad was electric - Jay-Jay Okocha’s sorcery, Nwankwo Kanu’s charisma, Celestine Babayaro’s daring runs, Sunday Oliseh’s thunderbolts from distance. And at the back, patrolling with warrior discipline and prophet-like calm, stood Taribo West.

They had arrived as outsiders. They left as immortals.

They went through the group stage and defeated Mexico in the quarter-finals, setting up a semi-final against a star-studded Brazil side boasting Ronaldo, Bebeto, Roberto Carlos and Juninho Paulista. Trailing 3-1 deep into the second half, they mounted a breathtaking comeback - scoring in the 78th and 90th minutes before Kanu struck a golden goal in extra time. The 4-3 win became an instant classic.

In the final, Argentina awaited: Crespo, Ortega, Simeone, Claudio López. Again, Nigeria fell behind. Again, they clawed their way back. And again, they found a winner late - Emmanuel Amuneke striking in the 90th minute to seal a 3-2 victory.

The streets of Lagos erupted. An entire continent celebrated. This was more than gold. It was validation. It was revolution.

Always the first to kneel in prayer before kick-off, Taribo West played every minute of the tournament. His influence went beyond defending - he was a force, spiritual, physical and psychological, anchoring Nigeria’s miracle with faith as much as with tackles.

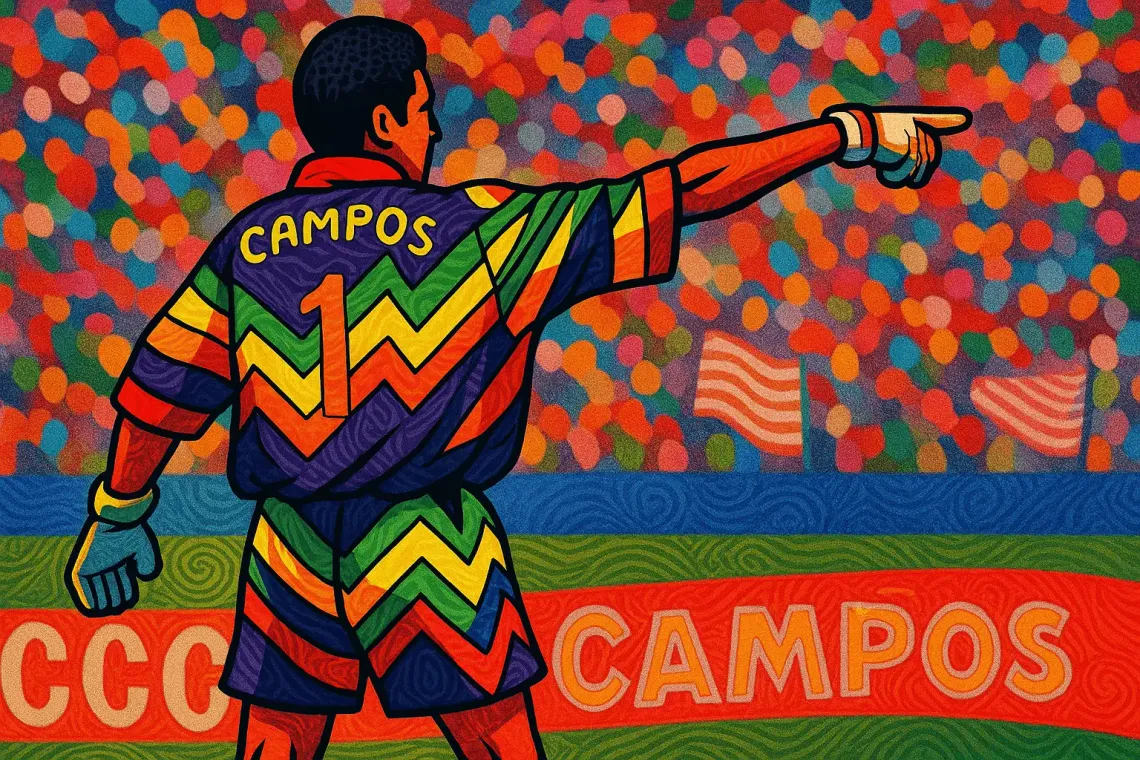

The Inter Milan years

In 1997, Taribo West joined Inter Milan for a reported €3.5 million, stepping into the cauldron of Serie A’s golden era. Inter had not won a Scudetto since 1989, but they were investing heavily to end the drought: Ronaldo arrived as the most expensive player in the world, Diego Simeone brought steel, Paulo Sousa brains, while Youri Djorkaeff and Álvaro Recoba added flair.

Taribo came with a reputation: he had been part of Auxerre’s fairy-tale double in France, and at Atlanta ’96 he anchored Nigeria’s Olympic miracle. Two golden stories already - could he deliver a third, this time in Milan?

For a moment, it looked like destiny. In his first season, Inter finished second in Serie A and conquered Europe by winning the 1998 UEFA Cup. Taribo was in the starting XI for the final in Paris, a 3-0 demolition of Lazio, and earlier he had scored a vital extra-time goal in the quarter-final against Schalke 04. The Nigerian with the green braids was living the dream.

But the following campaign was nearly the opposite: 1998-99 was a season mired in chaos. Inter went through four different coaches: Luigi Simoni was replaced in November, then Mircea Lucescu took over, later Luciano Castellini, and finally Roy Hodgson tried to steer the ship. The instability at the top mirrored a lackluster league performance - Inter finished 8th in Serie A and missed out on UEFA competition.

Even amid the turmoil, West still made 21 league appearances that season - a sign that despite everything, he remained part of the core lineup. The club did make a respectable run in continental competition, reaching the Champions League quarterfinals before falling to Manchester United.

But in the middle of those two contrasting seasons, Nigeria’s golden generation looked beyond club football. They wanted to build on the promise of USA ’94 and the glory of Atlanta ’96. It was time for the 1998 World Cup.

France ’98: Promise and heartbreak

For Nigeria’s golden generation, the 1998 World Cup in France was supposed to be the summit. Four years earlier, still without West, they had dazzled in the United States, reaching the Round of 16 before falling to Italy in extra time. Two years later, they conquered the world at the Atlanta Olympics. France was meant to be the next step - the chance to prove that an African team could challenge for the greatest prize of all. At the helm was a man who knew a lot about African teams’ deep runs: Bora Milutinović.

Their opening match against Spain in Nantes on 13 June was one of the tournament’s instant classics. Trailing twice, Nigeria fought back to win 3-2 thanks to Oliseh’s 25-yard rocket that shook the net - and shook the hierarchy of international football. Suddenly, the Super Eagles were front-page news, seen not just as entertainers but as contenders.

A 1-0 victory over Bulgaria followed, with Victor Ikpeba scoring the only goal. Qualification for the knockout stage was sealed with a game to spare. Nigeria rotated heavily in the final group match and lost 3-1 to Paraguay, but they still topped Group D, finishing ahead of Spain. For a team from Africa, this was unprecedented territory: back-to-back tournaments advancing from the group, now with the world’s attention firmly upon them.

The Round of 16 paired Nigeria with Michael Laudrup’s Denmark in Paris, marshalled at the back by Peter Schmeichel. On paper, the Super Eagles were favourites. The Danes had struggled in their group, and Nigeria looked primed for another deep run. But football doesn’t follow scripts.

From the first whistle, Denmark suffocated Nigeria with pressing and direct play. By the 12th minute it was already 2-0. Denmark scored twice more in the second half before Babangida pulled one back. Taribo and the defence looked shell-shocked, unable to contain Brian Laudrup’s movement and Ebbe Sand’s sharp finishing. Nigeria’s dream ended in a 4-1 defeat - abrupt, brutal, and heartbreaking.

For Taribo West, the tournament was bittersweet. He had played every match, his unmistakable braids and uncompromising style symbolic of Nigeria’s rise. But he also stood on the pitch at the Stade de France as the dream crumbled.

Nigeria had promised the world, and for two weeks they delivered - joy, goals, belief. Yet when the knockout stage arrived, they faltered. It was a cruel reminder that talent and flair alone could not yet break through football’s old order.

For West and his teammates, France ’98 was both validation and a warning. They had shown Africa could stand toe-to-toe with Europe and South America, but they also discovered how fragile dreams can be on the biggest stage.

The Downfall

After two turbulent but memorable seasons at Inter, Taribo West entered the 1999-2000 campaign under new coach Marcello Lippi. But in Lippi’s blueprint, there was no place for him. The defence was rebuilt around Ivan Córdoba’s speed and Laurent Blanc’s experience, leaving West frozen out. He did not play a single league match that autumn. By January, his Inter adventure was over.

Then came the shock. In the winter transfer window, Taribo crossed the divide to Inter’s fiercest rivals, AC Milan. For a player whose green braids had become synonymous with the blue-and-black, the move was jarring. Yet it promised a fresh start in the same city.

But San Siro’s red half never warmed to him. West made only a handful of appearances before being pushed to the margins. Later, he would allege that it was not simply footballing reasons but darker forces at play. In an interview years after, Taribo claimed the Mafia had intervened in his career, that club doctors were bribed to label him injured, and that powerful figures in Italian football wanted him out. “They didn’t want an African player taking the place of an Italian one,” he said.

By the end of that season, he was on loan at Derby County, fighting relegation in the Premier League. The trajectory was unmistakeable: from European finals to survival scraps.

The wanderings continued. He had a short stint at Kaiserslautern in Germany, followed by a brief renaissance at Partizan Belgrade, where he lifted a league title and even tasted the Champions League again. Then came shorter, quieter spells - Al-Arabi in Qatar, Paykan in Iran, Plymouth Argyle in England.

Each move felt further from the grand stages where he had once gone shoulder to shoulder with the likes of Batistuta, Del Piero, and Shevchenko.

But even as his club career began to fragment, his place in the national team remained unshaken. And so, in the summer of 2002, while at Partizan - 28 on paper, possibly 40 in reality - Taribo West boarded the plane for one last World Cup: Korea-Japan 2002.

Korea-Japan 2002: The End of the Road

The 2002 World Cup was historic for many reasons. It was the first to be hosted in Asia, the first co-hosted by two countries, and the first time traditional giants like France and Argentina crumbled in the group stage.

But for Nigeria, it marked the end of a golden cycle. The team that had danced through Atlanta and stormed France in 1998 arrived fractured - weighed down by political interference, poor preparation, and aging legs.

Taribo West, still unmistakeable with his braids, partnered Joseph Yobo in defence, trying to hold together a side that no longer had the same verve or belief. Jay-Jay Okocha still tried to pull strings, but Kanu was a shadow of his former self, and the coaching staff seemed paralysed by indecision.

Drawn in the so-called group of death, Nigeria lost narrowly to Argentina in the opening match, courtesy of a Gabriel Batistuta header. They went ahead against Sweden but two Henrik Larsson goals gave Sweden the win. A draw against England in the final group game earned some dignity, but wasn’t enough to avoid being bottom of the group.

West had played the first two matches. It was not a disaster, but it was a certainly a comedown. There would be no miracle run this time.

But even in decline, he had gone to war for his country one last time - and few defenders in Nigerian history can claim to have left a deeper mark.

Stuff of Legend

Taribo West retired in 2008 - officially at 34, possibly at 46.

But age, in his case, was never the number that mattered most. He wasn’t built on stats or spreadsheets. He was built on presence.

West was not the kind of defender you outmanoeuvred. He was the kind you tried to escape from. Raw, but rarely reckless. Combative, but not clumsy. He read danger early, loved a sliding challenge, and didn’t mind if he took the ball and the man into the advertising boards at once. He was strong in the air, surprisingly quick over short distances, and physically dominant even by Serie A standards. But above all, he played with an unshakable sense of belief - a conviction, bone-deep and unshifting, that he belonged. That he was better.

One Nigerian documentary captured it simply: “West had an unshakable confidence that intimidated opponents. That belief radiated through those braids.”

Even the greatest strikers struggled to shake him. Thierry Henry, when asked who he least liked playing against, didn’t hesitate: “Taribo West. He followed me everywhere. Even in the dressing room.” Henry wasn’t joking. It wasn’t just man-marking. It was obsession. West didn’t just shadow his opponents - he hunted them.

And then there was the age. In 2013, Žarko Zečević, an executive at Partizan Belgrade, said out loud what many had whispered for years. “He said he was 28 when he signed. We later discovered he was 40.” But then came the line that truly mattered:

He still played well.

That’s the truth of Taribo West. Whether he was 28 or 40, whether he bent the rules or not, he played with conviction. He played with fury. He defended with intent, urgency, and total commitment. And for those who watched him - knees high, chest out, braids blazing - that’s what we’ll remember.

Not the paperwork.

The presence.

And that presence still lives in football’s collective memory.

Subscribe to our newsletter and get our news in your inbox

Member discussion