Growing up in Lisbon, during my high school years, I briefly had a romanian classmate - at the time, a distant and mysterious country somewhere in Eastern Europe. We got along well, and through that friendship a quiet fondness for Romania began to take root in me, long before I ever set foot there. I would only visit in my thirties, but the seed had already been planted.

So when the 1994 World Cup came around, and with my Portugal absent from the tournament, Romania became one of the teams I rooted for. And what a choice that turned out to be. That side - Hagi weaving magic, Dumitrescu gliding past defenders, Răducioiu scoring with ease - remains one of my dream teams. Yet further back, almost unnoticed, stood a thirty-year-old libero. Elegant. Sober. A quiet kind of class, with a serenity that seemed unshakable.

How could it have been otherwise? At the time I had no idea, but years later I learned the truth: after all Belodedici had endured under a dictatorship, after risking his life to escape, playing at the back of that golden Romanian team must have felt like one of the easier tasks of his life.

This is the story of Miodrag Belodedici - the only man to win the European Cup with two Eastern clubs, a player condemned as a traitor by his homeland, and a symbol of how football can transcend borders, regimes and repression.

Becoming a Libero

Miodrag Belodedici was born in 1964 in Socol, a small village on the banks of the Danube. It was a frontier town, where Romania touched Yugoslavia, and his family belonged to the country’s small Serbian minority. In Ceaușescu’s Romania, such origins mattered. Ethnic minorities lived under suspicion, regarded as potential sympathisers of neighbouring states rather than loyal Romanians.

If you are not familiar with this dictatorship, here is a very short introduction: Nicolae Ceaușescu had ruled Romania since 1965, a dictator who turned everyday life into a theatre of shortages and suspicion. Electricity was cut, petrol rationed, bread scarce. The Securitate, his omnipresent secret police, kept watch over every conversation. For most Romanians the world felt grey, claustrophobic, and inescapable. Yet Ceaușescu adored sport, parading victories as proof that his system worked. Footballers were soldiers in this propaganda war - celebrated on the pitch, but never truly free.

Still, footballers enjoyed privileges denied to ordinary citizens. They travelled abroad when others could not, ate better thanks to club kitchens, and lived in relative comfort compared to a population surviving on rations. In return, they were expected to win, and to win for the regime.

Belodedici’s calm temperament and natural reading of the game soon made him stand out. By the early 1980s he had joined Steaua Bucharest, the club of the Romanian Army, the team favoured by the Ceaușescu family. At Steaua, players were technically ranked as officers. Their victories were paraded as proof of the regime’s strength, their failures as signs of weakness.

Within this militarised environment, Belodedici thrived in his own quiet way. He was no enforcer. He did not dive into tackles or roar at referees. He was a reader of the game, a libero in the truest sense: sweeping up behind defenders, stepping calmly out of defence, distributing the ball with a serenity that contrasted starkly with the chaos around him. In an era when Franco Baresi was redefining the sweeper’s art in Milan, Belodedici carried the torch for Eastern Europe. He was elegance in a world of brute force.

Steaua’s Impossible Triumph

By the mid-1980s, Steaua Bucharest were already a force at home. Founded as the Army’s club, they had won a clutch of Romanian league titles but had rarely made an impression on the European stage. Their best continental run had come in 1971-72, when they reached the quarter-finals of the Cup Winners’ Cup, only to be outclassed by Bayern Munich. In European Cup terms, they had never gone beyond the second round.

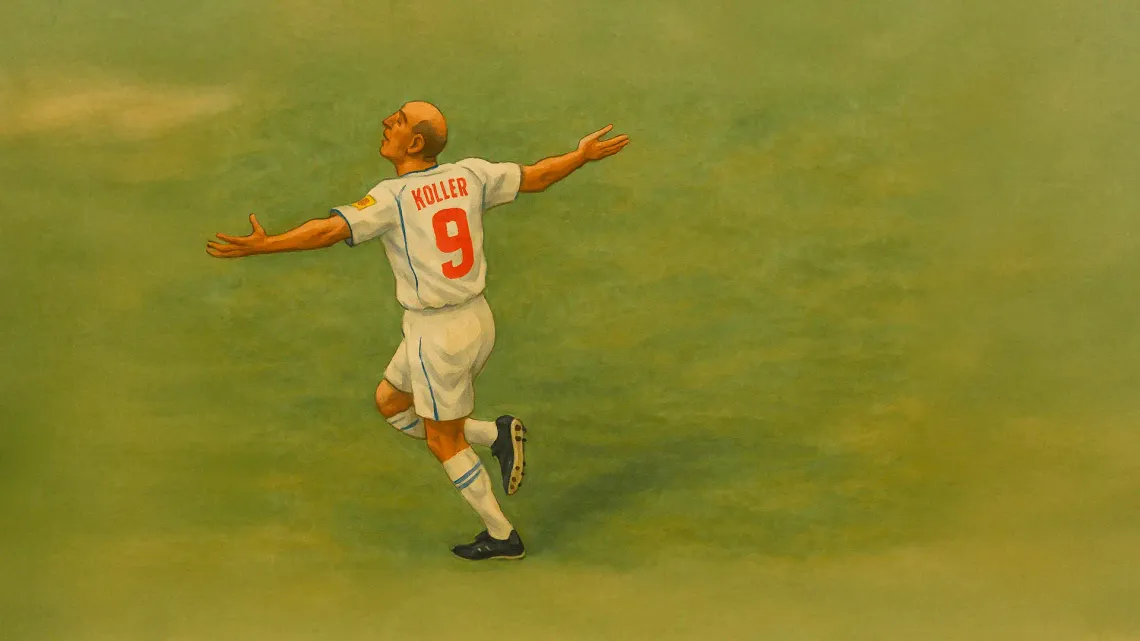

Domestically, however, Steaua were beginning to dominate. Under the guidance of Emerich Jenei, and with Ceaușescu’s patronage, they built a side of rare quality. László Bölöni, the intelligent midfielder; Marius Lăcătuș, the fiery winger; Gavril Balint, the clinical forward; Victor Pițurcă, the main striker; and, at the back, the composed libero Miodrag Belodedici. In goal was Helmuth Duckadam, a relatively unheralded keeper about to write himself into legend. This was not a team of global stars, but of disciplined, resourceful players shaped by an unforgiving system.

The European Cup of 1985-86 was a very different competition to today’s Champions League. It was a pure knockout tournament: two-legged ties from the first round all the way to the semi-finals, no group stages, no second chances. One bad night could eliminate you.

Steaua’s journey began in Denmark against Vejle. A solid 1-1 away draw was followed by a routine 4-1 victory in Bucharest. In the second round they faced Honvéd of Hungary, historically a giant of Eastern European football. A 1-0 win at home was enough, as they ground out a 1-1 draw in Budapest. The quarter-final brought Kuusysi Lahti of Finland, an unfancied opponent. Steaua made light work of them, winning 4-1 on aggregate.

The semi-final, however, was daunting: Anderlecht of Belgium, who had lifted the UEFA Cup just a few years earlier and boasted talents like Franky Vercauteren and Erwin Vandenbergh. In Brussels, Steaua lost 1-0, and their run looked over. Yet in Bucharest, spurred on by a fervent crowd and Ceaușescu’s presence in the stands, they turned it around, winning 3-0 to book a place in the final. For the first time, a Romanian club would contest the greatest prize in European football.

The final, played on 7 May 1986 at the Ramón Sánchez-Pizjuán in Seville, pitted them against Barcelona. The Catalans, with 70,000 fans behind them, were overwhelming favourites. Their squad was packed with international names: goalkeeper Urruti, German playmaker Bernd Schuster, Scottish striker Steve Archibald, and young talents such as Ángel Pedraza. Terry Venables, their English manager, had built a side that had recently won La Liga and now eyed Europe’s top trophy.

From the start, the match was a siege. Barcelona attacked relentlessly, urged on by the partisan crowd. Yet time and again they were repelled. Belodedici, sweeping calmly behind his defenders, intercepted and cleared with minimal fuss. Bölöni and Majearu shielded the defence, while Duckadam produced crucial saves. The longer it stayed goalless, the more the tension built. After 120 exhausting minutes, it remained 0-0.

Then came one of football’s most extraordinary penalty shoot-outs. Barcelona, weighed down by expectation, crumbled. Alexanko, Pedraza, Pichi and Marcos Alonso all stepped up. All four were denied. Duckadam, the “Hero of Seville”, saved every single penalty. For Steaua, Lăcătuș and Balint converted their spot-kicks, and that was enough. Against all odds, Steaua Bucharest were champions of Europe.

For Romania it was unprecedented. Steaua were the first Eastern European club to win the European Cup. In Bucharest, Nicolae Ceaușescu seized upon the triumph as proof of his regime’s superiority. He paraded the players as national heroes, their victory framed as a triumph of socialism and discipline over Western capitalism. For Eastern Europe, it was a rare moment of pride in a competition dominated by Western giants.

For the players, though, it was a paradox. They had achieved immortality on the pitch, but off it they remained under the control of the regime. They were champions of Europe, yet still prisoners of Ceaușescu’s Romania. And for Belodedici, calm and composed at the heart of the defence, it was the first step towards a legend that would stretch far beyond Seville.

The Desertion

To understand Belodedici’s escape, one must grasp the suffocating reality of 1980s Romania. Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship was a system of control and fear: rationing so severe that families queued for bread for hours, petrol restricted to 25 litres per car per month, electricity cut without warning. The Securitate, the secret police, kept one informer for every 1,500 citizens. People lived in a climate of suspicion, where even neighbours and relatives might be listening.

Football was a favoured propaganda weapon. Steaua Bucharest, owned by the Army, and Dinamo Bucharest, run by the Interior Ministry, were more than clubs - they were arms of state power. Matches between them were not just derbies but battles for influence within the regime. Success meant favour, failure meant punishment.

For players, freedom was an illusion. Nicolae Dobrin, perhaps Romania’s most gifted playmaker, saw a move to Real Madrid blocked. Ilie Balaci was prevented from joining AC Milan. Even Gheorghe Hagi, later celebrated worldwide as the “Maradona of the Carpathians”, could not leave until after the 1989 revolution. Footballers might travel abroad occasionally, but always under supervision, their passports confiscated the moment they returned.

Belodedici’s position was doubly precarious. As a Serbian Romanian, his loyalty was questioned. At Steaua, whispers followed him: he was not “fully Romanian”, not fully trusted. He had given the club its greatest triumph in Seville, yet still felt like an outsider in a system that valued obedience above all.

By late 1988, he had a plan. Romanians could apply for permission to travel abroad, a process that could take months, sometimes years, and was often rejected. Footballers, especially internationals, had a slightly easier path, their requests more likely to be granted if presented as family obligations. Belodedici used this loophole. Claiming that he and his mother needed to attend a relative’s wedding in Yugoslavia - a neighbouring communist state, though one far more relaxed than Ceaușescu’s Romania - he obtained the paperwork and was allowed to cross.

Once across the border, he never came back, immediately requesting asylum in Belgrade. His sister’s escape was even more perilous: she swam the Danube at night to reach the Yugoslav shore, knowing that Romanian border guards had orders to shoot deserters on sight. Belodedici was waiting for her on the other side.

The response from Bucharest was ferocious. He was branded a deserter, stripped of his Army rank, sentenced in absentia to ten years in prison for treason. The authorities even destroyed his Steaua contract, leaving him technically unregistered, and UEFA - caught between conflicting documents - suspended him for a year.

He was, of course, banned from the national team, which meant missing the 1990 World Cup. But before that, in 1989, he signed for Red Star Belgrade.

Refuge in Belgrade

For Belodedici, Red Star Belgrade was not just a refuge - it was destiny. Growing up in Socol, on the banks of the Danube, he was closer to Belgrade than to Bucharest, and as a child he listened to Yugoslav radio, secretly following the fortunes of Crvena Zvezda. They were the club of his dreams, a symbol of the footballing freedom he longed for across the border.

So when he crossed into Yugoslavia in December 1988, he didn’t arrive with an agent or a contract. He simply walked to the gates of the Marakana stadium, asked to see the club president, and introduced himself. “I’m Miodrag Belodedici. Can I play for your club?” Imagine it: a European Cup winner, one of the continent’s finest liberos, knocking on your office door and asking for a job. At first they thought it might be an impersonator - how could a Steaua star simply turn up on his own? But once he convinced them he was the real Miodrag Belodedici, they never looked back.

The timing could hardly have been more dramatic. Romania was still under Ceaușescu’s grip, but only just. A year later, in December 1989, the regime collapsed in bloody revolution. Ceaușescu and his wife were executed on Christmas Day, the footage broadcast across the world. The man who had called Belodedici a traitor was gone, and his sentence annulled. Belodedici, once a fugitive, was suddenly a free man - though his exile had already given him a new home in Belgrade.

Red Star were on the rise. In the mid-1980s they had been a powerhouse of Yugoslav football, winning league titles in 1980, 1981, 1984 and 1988, but in Europe they often stumbled at the final hurdles. In 1985 they reached the UEFA Cup semi-finals, falling to Köln. In 1987 they famously beat Real Madrid 4-2 at the Marakana, only to lose 2-0 in the Bernabéu and go out on away goals. There was always talent - Stojković, Prosinečki, Savićević - but never quite the finishing touch.

By 1990-91, the finishing touch had arrived. Belodedici, finally free after a year’s suspension, was anchoring the defence with elegance and composure. Around him was a multi-ethnic ensemble: Robert Prosinečki’s golden passes, Dejan Savićević’s audacity, Darko Pančev’s ruthless finishing, Siniša Mihajlović’s thunderous left foot, and Vladimir Jugović’s tireless industry. Together they became a multi-ethnic ensemble that symbolised Yugoslavia’s richness at a time when the country was edging towards tragedy.

Red Star’s Night in Bari

The 1990-91 European Cup was Red Star Belgrade’s moment of destiny, and it culminated in Bari on 29 May 1991.

Their run to the final was commanding. In the first round they swept aside Grasshoppers of Switzerland 5-2 on aggregate. In the second round they faced Rangers of Scotland, demolishing them 3-0 in Belgrade before a routine 1-1 draw in Glasgow. The quarter-finals brought Dynamo Dresden: Red Star won 3-0 in Belgrade, though the second leg in Germany was abandoned amid chaos provoked by German hooligans. UEFA awarded a 3-0 victory to Red Star, giving them a 6-0 aggregate.

The semi-final against Bayern Munich was pure theatre. This was an outstanding German side featuring Jürgen Kohler, Stefan Reuter, Olaf Thon, Stefan Effenberg, Markus Babbel and Brian Laudrup. In Munich, Red Star stunned their hosts, coming from 1-0 down to win 2-1 with goals from Pančev and Savićević. In Belgrade, with nearly 80,000 fans roaring them on, Red Star went ahead through a deflected free-kick from Siniša Mihajlović. But Bayern fought back, with Augenthaler and Manfred Bender scoring twice in five minutes to level the tie. With minutes remaining, Bayern struck the post - inches from killing Red Star’s dream. Then, in the 90th minute, Augenthaler, usually irreproachable, diverted a cross over Raimond Aumann and into his own net. It was destiny, written in the cruellest, most dramatic way.

In the final, at the Stadio San Nicola in Bari, they faced Bernard Tapie’s Olympique Marseille. The French, with Jean-Pierre Papin, Abedi Pelé and Chris Waddle, were the bookmakers’ favourites. Red Star, mindful of Marseille’s attacking power, played with caution, their defence - with Belodedici serene at sweeper - refusing to yield. For 120 minutes they absorbed pressure, slowing the tempo, waiting for penalties. Dragan Stojković, for many the greatest player Red Star ever produced and now at Marseille, was the one most Yugoslav players feared. He came on late in extra time, but the deadlock held.

The game went to penalties. Manuel Amoros, the experienced French right-back, missed Marseille’s first kick. Red Star, by contrast, were flawless: Mihajlović, Belodedici himself, Binic, Pančev and Prosinečki all converted. History was made - Red Star Belgrade were European champions, the last club from Eastern Europe ever to claim the crown.

For Belodedici it was personal vindication. He became the first player to win the European Cup with two different Eastern clubs. Months later, in Tokyo, Red Star defeated Colo-Colo to lift the Intercontinental Cup. From condemned traitor to twice a world champion, Belodedici’s story had gone beyond survival: it was triumph against history itself.

Yet as Belodedici celebrated his second European triumph, Yugoslavia itself was collapsing. In June 1991, barely weeks after Bari, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence, and war soon followed. The unity Red Star had symbolised on the pitch was about to be shattered off it. For Belodedici, the next step was away from the Balkans altogether - a move to Spain, where he would spend the next four years.

Spain and the Return to the Tricolour

The fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu in December 1989 transformed Romanian football overnight. Suddenly, the walls that had kept players imprisoned at home collapsed. What had once been blocked transfers and broken dreams now became a flood of departures. Gheorghe Popescu went first, to PSV Eindhoven, before making his way to Tottenham and Barcelona. Gheorghe Hagi, Romania’s talisman, dazzled briefly at Real Madrid before finding immortality at Galatasaray. Ilie Dumitrescu left Steaua for Tottenham Hotspur, Florin Răducioiu joined Bari and then AC Milan, and Dan Petrescu landed in Foggia but would later become a Chelsea legend. The diaspora of talent became Romania’s Golden Generation, suddenly scattered across Europe’s top leagues, tested against the best.

Belodedici, however, had already gone. In 1992 he joined Valencia, a club in transition but with history and ambition. Spanish football at the time was evolving, tactically modern, moving towards pressing and zonal defending. The libero role - the free sweeper he had mastered - was beginning to fade, replaced by the rigour of a flat back four.

At Valencia, Belodedici adapted with dignity. He played under the likes of Héctor Núñez and Guus Hiddink, sharing the dressing room with Fernando Giner, Quique Sánchez Flores and a young Gaizka Mendieta, while up front the goals of Predrag Mijatović and Luboslav Penev carried the side. Trophies eluded him, but he became a reliable, composed figure during his two seasons at Mestalla. Later he would represent Valladolid and Villarreal, lending his experience and authority to smaller clubs, always admired if not always celebrated.

By then, the door back to Romania had also reopened. In 1992, after four years of absence, Belodedici returned to the national team. His mere presence was symbolic: once branded a deserter and sentenced to prison in absentia, he now wore the tricolour again, this time as part of a liberated Romania. At 30 years old, with two European Cups behind him and the scars of history etched into his career, he was at the peak of his powers when Romania arrived in the United States for the 1994 World Cup.

Romania’s Golden Generation

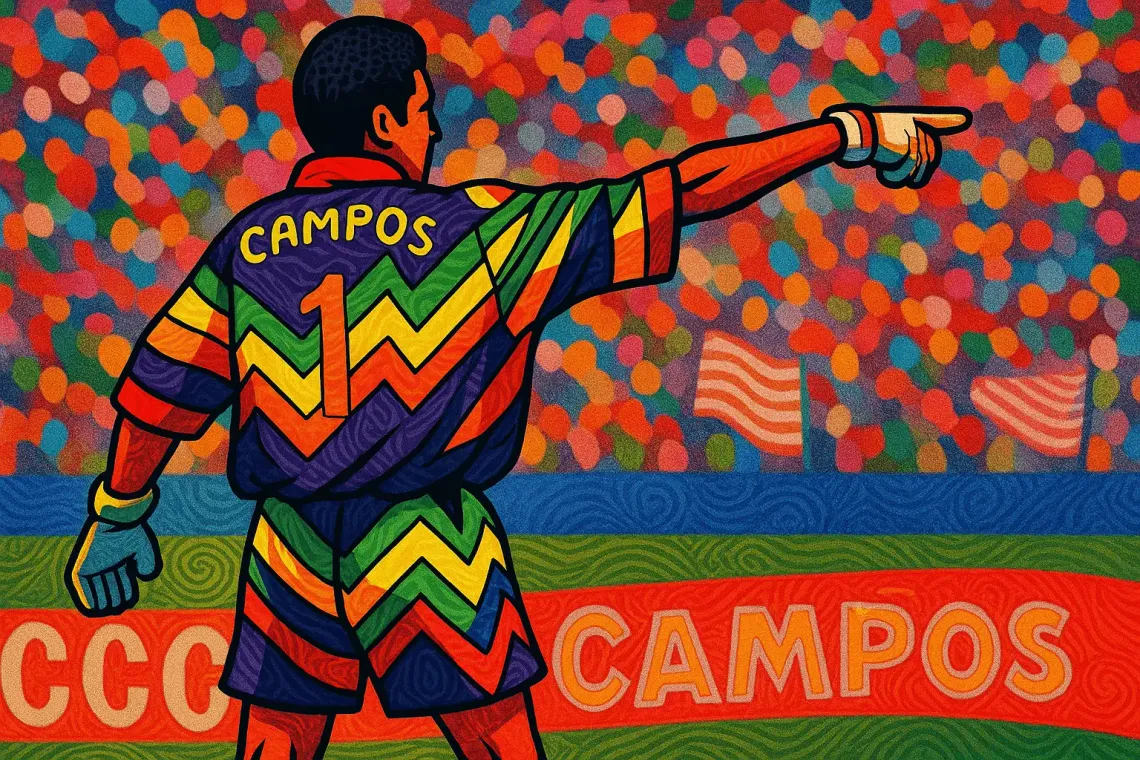

The 1994 World Cup in the United States was the summit of Romania’s Golden Generation. It was the stage where Gheorghe Hagi confirmed his genius to the world, Ilie Dumitrescu announced himself, and Florin Răducioiu, Dan Petrescu, Gheorghe Popescu and Miodrag Belodedici formed the spine of a team that briefly felt unstoppable, under the guidance of Anghel Iordănescu, who had previously coached Belodedici at Steaua.

Romania were drawn in Group A alongside Colombia, Switzerland and hosts USA. Their opening match in Pasadena set the tone. Colombia, led by Carlos Valderrama and Faustino Asprilla, were dark horses tipped by Pelé himself to win the tournament. Romania tore them apart. Răducioiu scored twice, Hagi added a stunning left-foot strike from distance that curled gloriously over Óscar Córdoba, and a 3-1 victory shook the World Cup.

But in the second match, the exuberance slipped. Against Switzerland in Detroit, Romania looked disorganised. Stéphane Chapuisat, Alain Sutter and Adrian Knup punished defensive lapses, and a 4-1 defeat brought them crashing back to earth. The final group game against the United States became a test of nerve. In front of a packed home crowd in Los Angeles, Petrescu scored the only goal, sealing a 1-0 win and top spot in the group.

Then came the masterpiece. In the round of 16, Romania faced Argentina - even without the suspended Diego Maradona, still a formidable side featuring Gabriel Batistuta, Claudio Caniggia, Diego Simeone, Ariel Ortega and Fernando Redondo. What followed in Pasadena was one of the World Cup’s greatest ever matches. It was already 2-1 inside the first 20 minutes: Ilie Dumitrescu scored twice - a curling free-kick and a cool finish after a Hagi through ball. Before that, Batistuta had equalised from the penalty spot. In the second half Hagi produced a moment of magic, racing down the left and drilling a low cross-shot inside the far post. Abel Balbo scored for Argentina to set up a nervous finale, but Romania held firm. Belodedici, elegant and unflappable, marshalled the back line while chaos erupted around him. At the final whistle it was 3-2 to Romania - the Carpathian fairy tale was alive.

The quarter-final against Sweden in Stanford carried all the tension of a nation on the brink of history. For 80 minutes it remained goalless, until Sweden’s Thomas Brolin struck from a clever free-kick routine. Romania refused to yield. Florin Răducioiu, tireless throughout the tournament, equalised in the 88th minute, sending the match to extra time. In the 101st minute he struck again, and Romania were suddenly ten minutes from a semi-final. But heartbreak followed: Kennet Andersson’s header made it 2-2, and penalties loomed.

In the shoot-out, Belodedici missed the decisive penalty and Romania’s dream was over. The Golden Generation had enchanted the world, but they had fallen one step short. For Belodedici, at 30, it was bittersweet: they had offered an incredible journey to a renewed Romania, yet it ended with the cruelty of his own miss.

Two years later, at Euro 96, the same generation landed in England but the magic was gone. Romania lost all three group matches - 1-0 to France, 2-1 to Bulgaria, and 2-1 to Spain. Belodedici, now 32, was still present in defence, but the spark of USA ’94 had faded. What had once looked like a team destined for greatness instead became a memory of what might have been.

That summer Belodedici made a surprising move to Atlante in Mexico, where he would later be joined by fellow countryman Ilie Dumitrescu. It was a world away from the glamour of European football, but he sought a new challenge. For the Romanian selectors, it was a step too far. Already 32 and with upcoming talents such as Tibor Ciobotariu and Iulian Filipescu emerging, he was omitted by Iordănescu from the squad for the 1998 World Cup in France.

Return to Bucharest

By 1998, a decade after fleeing Romania, he returned to Bucharest to close the circle. Back at Steaua, the club of his greatest triumphs and his most bitter memories, he was welcomed as a hero rather than a deserter. He won two more domestic league titles, reminding fans of the calm authority that had once made him Europe’s finest libero.

In 2000, at 36, he received an unexpected encore: a call-up to Euro 2000. Emerich Jenei, the coach who had led Steaua to the 1986 European triumph, was now in charge and knew Belodedici could still be useful.

Drawn in the group of death, Romania qualified alongside Portugal, leaving England and Germany behind. Used primarily as Gheorghe Popescu’s back-up, Belodedici still appeared against England and in the quarter-final against Italy - where Romania lost 2-0 to goals from Filippo Inzaghi and Francesco Totti - proving that even in his mid-thirties he retained the serenity and positional sense that had defined him throughout his career.

Belodedici retired in 2001. His career was unique. He was the only man ever to win the European Cup with two Eastern clubs - Steaua in 1986 and Red Star in 1991. He lived through dictatorship, exile, suspension, condemnation as a traitor, and yet returned to represent his country on the biggest stage.

As a footballer, he was elegance personified: the sweeper who never panicked, who read danger before others saw it. He belonged to a lineage of great liberos - Beckenbauer, Scirea, Baresi, Sammer - but his story was unlike any of theirs. His was marked by politics, ethnicity, and the constant shadow of the Securitate.

In Romania, he is remembered as both a survivor and a champion. In Serbia, he is revered as a Red Star legend. In football history, he stands as proof that even in the harshest political climates, the game could still produce moments of freedom.

Belodedici once admitted that leaving Romania was the hardest decision of his life, but that he knew he could not fulfil his dream otherwise. His courage ensured that his name lives forever. He was the libero who deserted - and in doing so, he conquered Europe.

Subscribe to our newsletter and get our news in your inbox

Member discussion