To me, Lev Yashin was never quite real. I never saw him play - he ended his career a decade before I was even born.

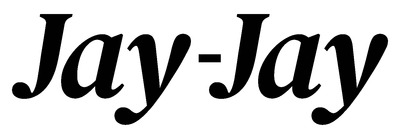

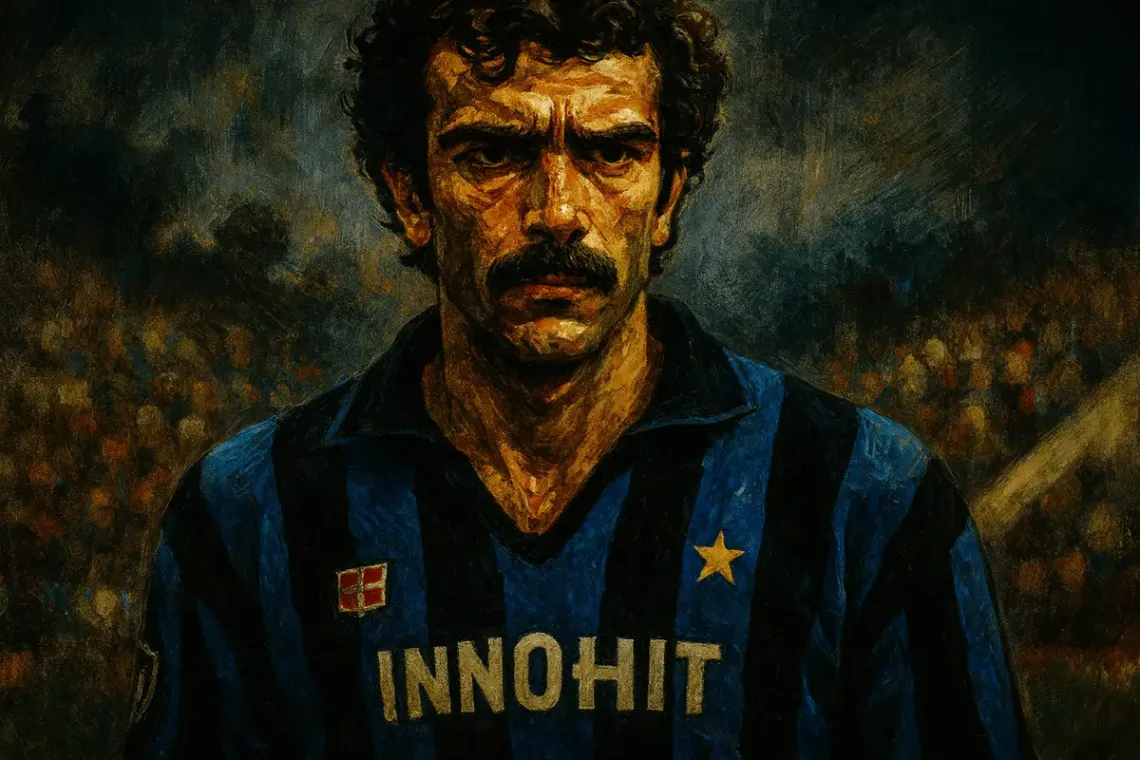

He was a creature from myth. A man dressed head-to-toe in black, always with a cap perched on his head or his hair perfectly parted. Leading a line of ice-cold soldiers with all those consonants - CCCP - stamped across their chests. So Mysterious. So intimidating.

I was always drawn to players who stood out. Who had a presence. Who were different. And Yashin was all of that, even in old photos.

The first time I saw an image of him - black kit, fierce stare, impeccable style - I wasn’t sure if I was looking at a footballer or a black-and-white movie star.

Now, let’s dive into his story and try to understand how a man from another era is still considered the greatest goalkeeper who ever lived.

Forged in hardship (1929-1948)

Lev Ivanovich Yashin was born on 22 October 1929, in a working-class district of Moscow, during Stalin’s brutal industrial push. His family were factory workers. And at just 12 years old, in the heart of World War II, Yashin was pulled from school and sent to work assembling weapons in a military factory.

The work was exhausting. The conditions - extreme. By the age of 18, Yashin collapsed emotionally. He suffered what he would later describe as a nervous breakdown. He stopped attending work, lost interest in sport, and felt nothing but emptiness. “Something inside me broke,” he would say.

In the rigid Soviet system, not showing up for work was a criminal offence. He was, briefly, considered a social outcast.

But fate intervened. A friend suggested he volunteer for military service, giving him structure, escape, and - crucially - time to rediscover football. It was during this period that he began playing again, and caught the eye of Arkady Chernyshev, a coach at Dynamo Moscow.

A legend was about to be born.

Becoming the Black Spider (1949-1971)

Yashin joined Dynamo in 1949, aged 20. It would remain his club for life.

Early on, he was far from the finished article. He made his debut in 1950 but spent years in the shadows, behind war hero Aleksei “The Tiger” Khomich. Yashin didn’t become first choice until 1953, at age 24.

Once he did, he never looked back.

He would go on to win five Soviet league titles (1954, 1955, 1957, 1959, 1963) and three Soviet Cups (1953, 1967, 1970), playing a total of 812 official matches with 270 clean sheets - or over 400, some sources say. He saved over 150 penalties, a world record. In 1963 alone, Dynamo conceded just 14 goals in 38 games - only 6 when Yashin was between the posts.

But stats alone don’t make legends. Style does.

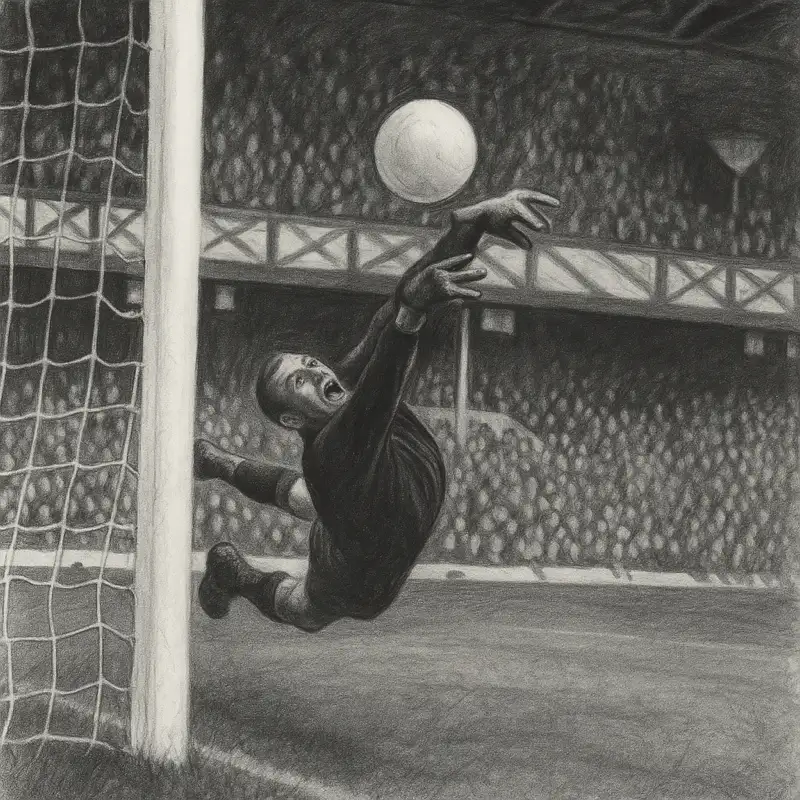

Yashin’s iconic black kit, his cap, and his vocal authority made him look like a general on the field. He changed the role of goalkeeper entirely - rushing off his line, intercepting crosses, organising his defence, launching counter-attacks. He was a sweeper-keeper decades before the term existed. A man who gave the position a third dimension, in his own words.

Yashin was inspired by Bulgaria’s Apostol Sokolov, one of the first keepers to step off his line and command his box. But it was Yashin who turned that boldness into a philosophy - and made it global.

A Soviet hero on the world stage (1954-1970)

Yashin made his debut for the Soviet national team in 1954, and it didn’t take long for his presence to elevate the entire squad.

In 1956, at the Melbourne Olympics, he helped the USSR win gold, conceding just two goals in five matches. It was a symbolic triumph - not just for the team, but for Soviet ideology on the global stage.

In 1960, he stood tall as the USSR claimed the inaugural European Championship, defeating Yugoslavia 2-1 in the final in Paris. Yashin was immense throughout, especially in the semi-final against Czechoslovakia, where he delivered a masterclass in control and composure. The win confirmed the USSR as a dominant force - and Yashin as the world’s best goalkeeper.

But it was in the World Cup, football’s true crucible, where Yashin’s legend took on deeper tones - glory, disappointment, redemption.

1958 - Sweden

Yashin, 28, made his World Cup debut. The Soviet Union were in Group 4, alongside Brazil, England and Austria. They beat Austria (2-0), drew with England (2-2), and lost to Brazil (0-2). That defeat introduced the world to a 17-year-old Pelé, who dazzled the tournament.

After the match, Yashin was so impressed that he reportedly called Pelé “The King of Football” - a nickname that would outlive them both.

The USSR advanced to the quarter-finals, where they were beaten 1-0 by Sweden, the host nation. It was a respectable run - and a warning that the Soviets had arrived.

1962 - Chile

This was supposed to be their next step. Yashin, now 32, was still the undisputed number one, and the USSR topped their group with two wins (vs Yugoslavia and Uruguay) and a dramatic 4-4 draw with Colombia.

But that Colombia match left scars.

Yashin conceded directly from a corner - an Olympic goal, the only one ever scored at a World Cup. He also played part of the match with a concussion, after being hit in the head by a fierce shot. Substitutions weren’t allowed at the time. He soldiered on.

In the quarter-final, against hosts Chile, things unravelled. The USSR lost 2-1 in Santiago. The match was physical, the atmosphere hostile. Yashin was blamed for the defeat, despite the Soviet defence looking disorganised throughout.

At home, the backlash was intense. He received hate mail, and some critics questioned whether his best days were behind him.

It was, by his own admission, the lowest point of his career.

1966 - England

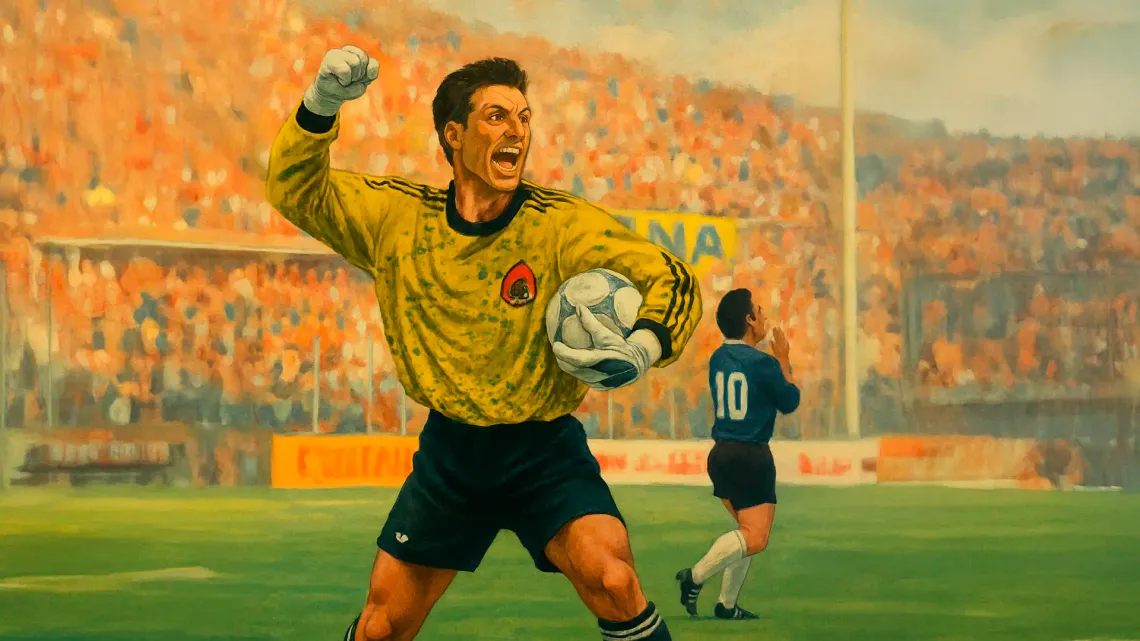

Redemption came four years later.

At 36, an age when most keepers had long retired, Yashin reclaimed his place and led the USSR to their greatest World Cup finish.

The Soviets won all three group games - beating North Korea, Italy, and Chile - and then defeated Hungary 2-1 in the quarter-finals.

In the semi-final, they met West Germany, and despite a valiant performance, they were beaten 2-1. In the third-place match, Yashin was rested, and the USSR lost 2-1 to Portugal - led by the irrepressible Eusébio.

Still, fourth place was a remarkable achievement. And for Yashin, it was personal vindication.

He had been written off. He answered with steel, poise, and one last glorious run.

1970 - Mexico

At 40, Yashin was no longer the starting keeper, but he still travelled to Mexico - officially as backup and assistant coach, unofficially as a father figure.

The USSR, with a new generation, advanced to the quarter-finals again, where they lost 1-0 to Uruguay in extra time. Yashin didn’t play, but his presence on the bench - and in the dressing room - was vital.

It was his fourth World Cup. No Soviet player ever played in more. None ever would.

The People’s Goalkeeper: A Soviet Icon

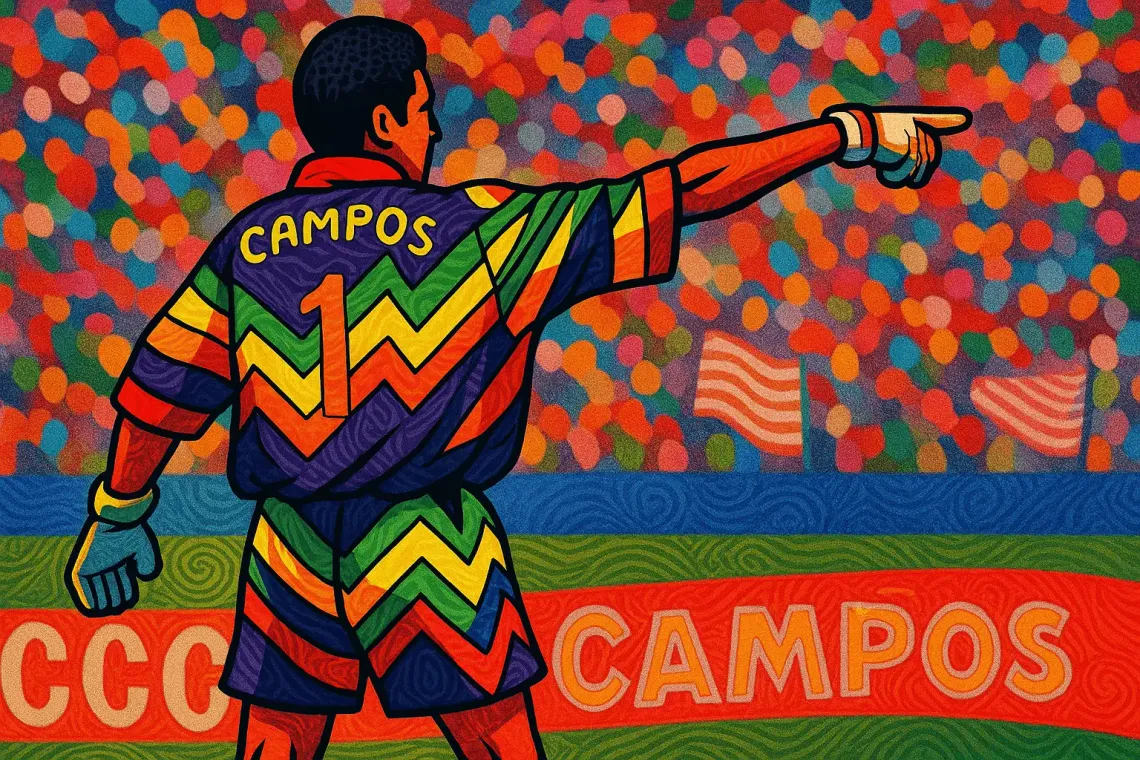

Lev Yashin wasn’t just a footballer. He was a political instrument - and he knew it.

In 1957, amid Khrushchev’s “Thaw”, Yashin became a member of the Communist Party. His loyalty to Dynamo Moscow - the club of the KGB - and his refusal to play abroad, made him a poster boy for Soviet values.

“I cannot imagine living anywhere else,” he once said. That alone was a message to the West.

His Olympic gold in 1956 and Euro 1960 title were paraded as proof of communist superiority. In 1963, when he won the Ballon d’Or, he wasn’t just celebrated as an athlete - he was hailed as a national treasure.

In 1967, the Kremlin awarded him the Order of Lenin - the USSR’s highest honour. And in 1990, months before his death, he received the Hero of Socialist Labour medal. Gorbachev didn’t attend in person - he sent a deputy. The gesture was symbolic: Yashin’s myth had already outlived the system.

Even after the fall of the USSR, Yashin’s face was chosen for the 2018 World Cup poster - a nostalgic return to the glory of a nation that once believed its athletes were warriors of ideology.

A Ballon d’Or for the ages (1963)

In 1963, Yashin did the impossible: he won the Ballon d’Or, the only goalkeeper ever to do so.

That same year, he starred in a Rest of the World XI vs England match at Wembley, making stunning saves in a 2-1 win. He was 34. The world stood in awe.

He later earned:

- Best Goalkeeper of the 20th Century (FIFA & IFFHS)

- European Goalkeeper of the Year - 9 times

- Namesake of the Yashin Trophy and World Cup Golden Glove

Flaws, myth and mortality

For all his glory, Yashin remained flawed - and human.

He smoked before matches. He drank vodka to calm his nerves. “A penalty save,” he once said, “is not just a save - it’s a shot at your soul.”

He occasionally played as a striker in reserve matches. But most myths around him only grew because people wanted them to. He looked like folklore. A footballer sculpted by Soviet realism and imagination alike.

But even folklore can’t protect you from life.

In 1986, due to circulatory issues, he had a leg amputated. He died in 1990, aged 60, from stomach cancer - just before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

He was given a state funeral. Few athletes ever earned that.

Eternal

Lev Yashin’s shadow still stretches across every football pitch.

Gordon Banks said:

“He was the model. Everyone looked up to him. I certainly did.”

Gianluigi Buffon added:

“He didn’t play the position - he redefined it.”

Even in death, Yashin remains the archetype. The man in black. The Black Spider. The last and greatest of football’s goalkeeping gods.

Back to the myth

When I first saw Yashin in that black kit, I didn’t see a footballer. I saw a symbol. A legend. A man who had stepped out of another world.

Now that I know the truth - the breakdown at 18, the propaganda, the pressure, the reinvention of his entire role - I’m even more in awe.

What’s truly remarkable is that this wasn’t some fantasy figure from a comic book.

He was a real man - born into the brutal machinery of Soviet communism, raised in a factory during wartime, buried under political expectations, worshipped at home, watched suspiciously abroad.

And somehow, through all of it, he found a way not just to cope - but to rise.

To redefine what a goalkeeper could be.

And to be remembered, across borders and generations, as the greatest who ever lived.

Subscribe to our newsletter and get our news in your inbox

Member discussion