In Portugal there’s a phrase from my childhood that still gets muttered whenever football feels unjust: Mão de Vata. It refers to the second leg of the 1990 European Cup semi-final. Marseille had beaten Benfica 2-1 at the Vélodrome; in Lisbon, a heaving 120,000 at the old Estádio da Luz watched Benfica edge it 1-0 when Vata, meeting Valdo’s corner, guided the ball in with his forearm. The referee pointed to the centre spot, and a catchphrase was born - our local echo of Maradona’s Hand of God.

For Marseille, that injustice became part of their folklore. Benfica lost the final to Milan, but the sense lingered that OM had been robbed of their rightful destiny. They came back and reached the final in 1991, just to fall to Red Star Belgrade on penalties. But in 1993 they climbed to the summit, beating Milan 1-0 in Munich and planting a flag for France on the European peak - only for the mountain to collapse beneath their feet.

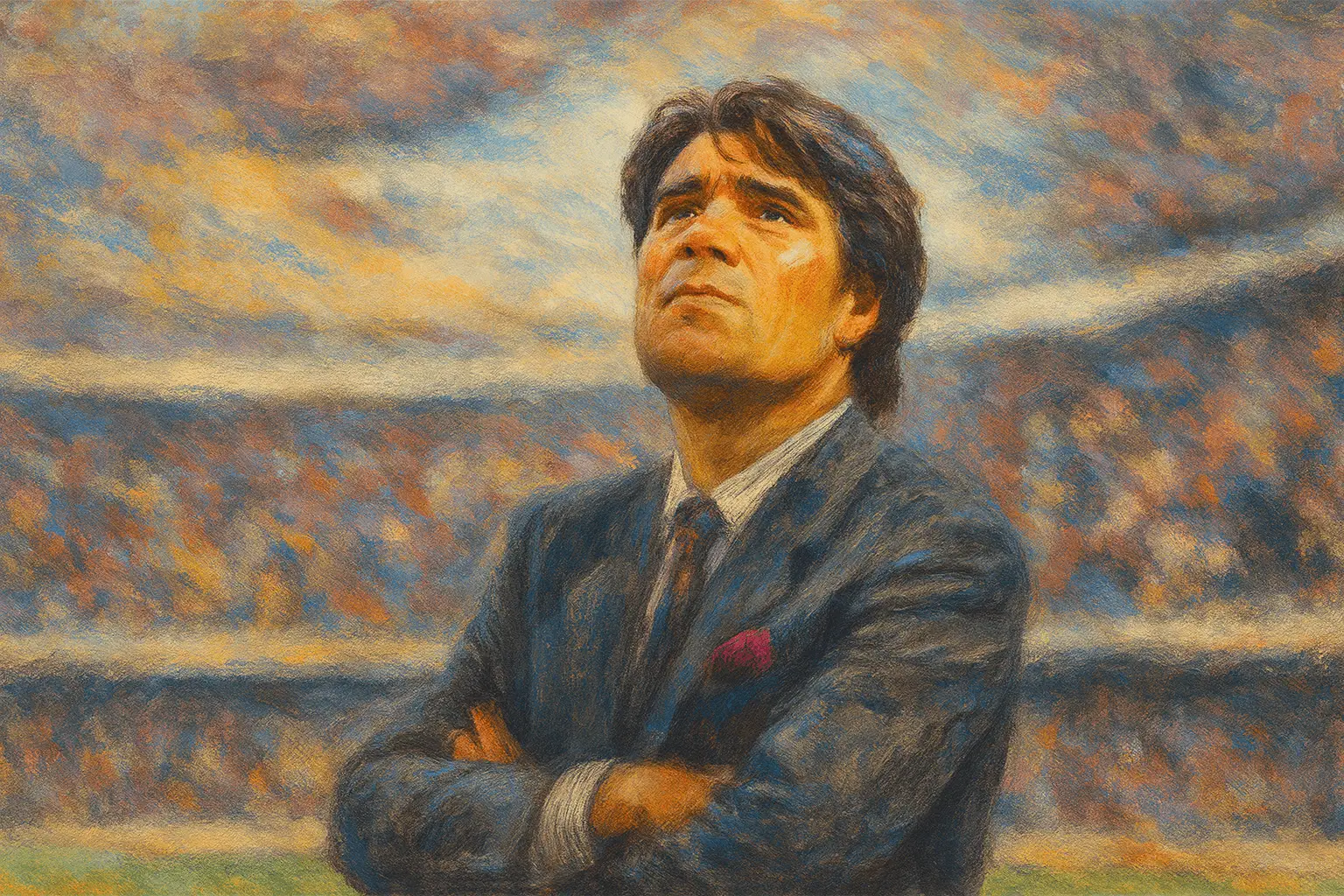

Under Bernard Tapie, Olympique de Marseille became a super-club forged by chequebook and nerve. Cash and courage, deals and denials, triumphs and scandal: the whole reign felt like cinema. Time to revisit those wild years in the south of France.

The One-Franc Takeover

By the spring of 1986, Olympique de Marseille were adrift. The Vélodrome still boiled with passion - loud, angry, romantic - but the club had lost its way. They had just finished 12th in the league, and the last league title, back in 1972, already felt like ancient history. A generation had grown up on memories rather than medals.

But Marseille was never just a football club. It was a mirror of the city - fiercely southern, proudly separate from the Parisian centre. A port city built by waves of immigrants, dockers and dreamers, Marseille had long carried a chip on its shoulder: culturally vibrant, economically unstable, and politically marginalised. In football, as in life, it wanted to matter.

Into that setting stepped Bernard Tapie - Parisian by birth, Marseillais by ambition. A self-made millionaire, son of a plumber, he had built his fortune buying bankrupt companies, turning them around, and selling them for profit. But he was more than just a businessman. By the mid-1980s, Tapie was already a television star, a host, a singer, a larger-than-life performer who blurred the lines between entrepreneur and entertainer. He had charm, ego, and a talent for turning failure into applause.

In April 1986, at the age of 43, Tapie took control of OM for a symbolic price: one franc. In truth, he assumed the club’s spiralling debts and its political baggage. But it wasn’t a transaction. It was a coup de théâtre. Tapie didn’t just buy a football club - he seized the stage of southern France.

He spoke the city’s language, even if he wasn’t born there: rêve, risque et rire - dream, risk and laughter. And he matched Marseille’s energy with a vision of his own. He didn’t want slow projects or quiet patience. He wanted names on posters, goals on highlight reels, and trophies on display. He wanted to win - and to be seen winning.

By 1990, Tapie’s empire included 80% of Adidas, acquired through a complex deal worth around 1.6 billion francs - roughly €440 million today, almost entirely financed through bank loans. It was a headline - making move, one that fed his myth as a visionary, a moderniser, a man who could cross industries as easily as he crossed cameras.

But the higher the climb, the steeper the fall. The Adidas deal made him more powerful, but also more vulnerable. The repayment schedules, the interest rates, the growing tensions between politics and finance - all of it would come back to haunt him. For now, though, Marseille believed. The one-franc takeover had become a revolution.

Tapie wasn’t just rebuilding a football club. He was giving a city back its pride. And that, in Marseille, is more valuable than any balance sheet.

Architects and Artists

Empires need architects. Tapie cycled through managers - Gérard Gili, then Franz Beckenbauer - before settling, in 1990, on Raymond Goethals, the wily and world-weary tactician who would take Marseille to the summit. Nearly seventy and rarely seen without a cigarette, Goethals brought a lifetime of know-how: former Belgium national coach, domestic titles with Anderlecht and Standard Liège, and a man who had once stood at the edge of scandal himself - implicated in the Standard-Waterschei affair before the 1982 Cup Winners’ Cup final. In Marseille, his name came with baggage, but also with muscle. He knew what it meant to chase glory without blinking.

So did Tapie.

On the pitch, the casting dazzled. Jean-Pierre Papin came from Club Brugge after Mexico ’86 and became a phenomenon: six consecutive Ligue 1 Golden Boots, a Ballon d’Or in 1991, and a world-record transfer to AC Milan in 1992 for £10 million. Chris Waddle arrived from Tottenham in 1989 for £4.5 million, and lit up the wing with his sway and imagination. Didier Deschamps, signed from Nantes in late 1989, captained the team in his early twenties. Basile Boli joined in 1990 and would soon write his name into club folklore with a single header. Marcel Desailly followed in 1992, a colossus from Nantes. Fabien Barthez, signed from Toulouse, was a fearless 21-year-old in goal.

To replace Papin, Tapie moved aggressively. Alen Bokšić came in from Cannes, Rudi Völler from Roma. The squad became a mosaic of talent, temperament and ego. Not every piece fit. Eric Cantona clashed with the club hierarchy and was gone before his genius could fully ignite. Enzo Francescoli, elegant but introverted, never truly found his rhythm. But Tapie’s hit rate was extraordinary.

And so were his methods.

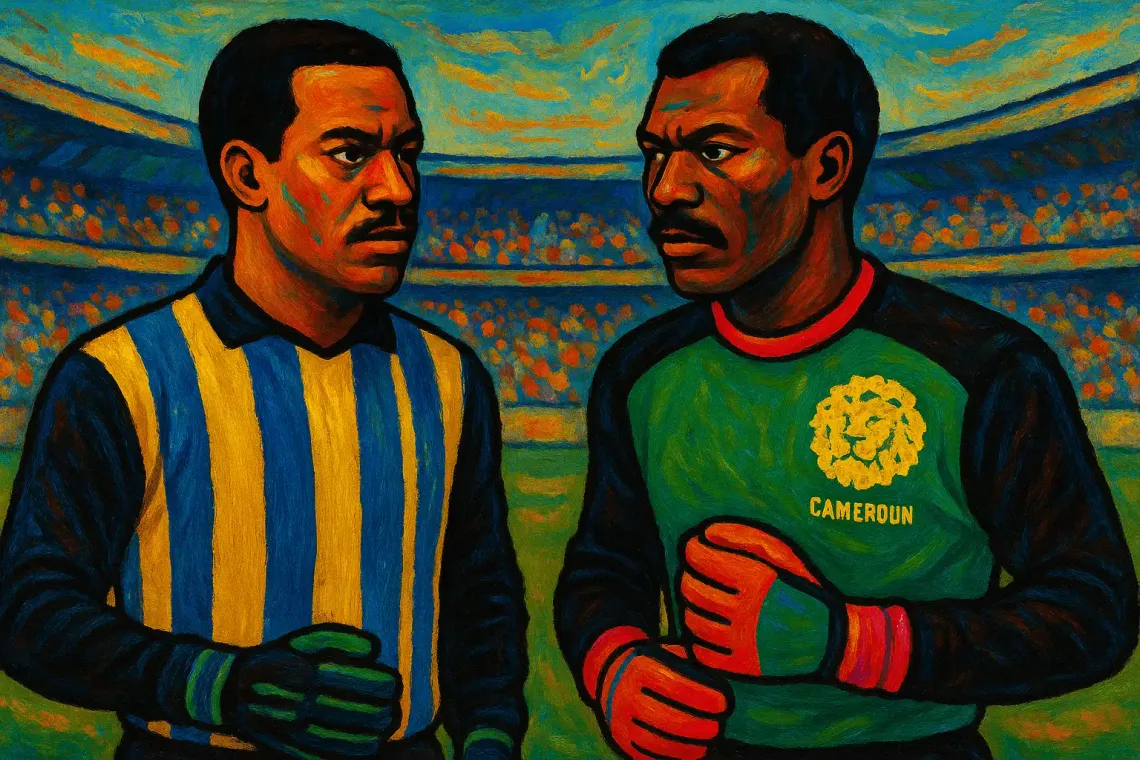

He didn’t just sign players - he outmanoeuvred rivals. He played the market with charm when it suited him, and with force when it didn’t. One deal became emblematic of his approach: when pursuing Abedi Pelé from Mulhouse, Tapie’s camp deliberately leaked a rumour that the Ghanaian had tested HIV-positive, a fabrication designed to scare off AS Monaco. In a climate still gripped by fear around AIDS, it worked. Marseille signed him unopposed. Years later, Tapie admitted he felt shame. But not regret. “Victory mattered more,” he said. That contradiction was his signature - ruthlessness justified by results.

Marseille played the same way: direct, quick, unapologetic. They didn’t wear teams down - they struck through them. The numbers told the story: four consecutive French titles from 1988-89 to 1991-92, and a fifth won on the pitch in 1992-93, later erased by scandal. But for a time, they ruled. Tapie didn’t just build a team. He built an empire. And like all empires, it lived on the edge of collapse.

Munich 1993

Before triumph, there were trials. In 1990, it was Vata’s hand that denied them in Lisbon. In 1991, they arrived in Bari as favourites and left with silence - beaten by Red Star Belgrade in a final that suffocated for 120 minutes and was decided on penalties. Even the 1991 Super Cup against Milan hinted at a rivalry yet to fully ignite. But each defeat taught Marseille how to win: how to kill space, when to slow the game, when to strike. Recruitment became more ruthless. The team matured. Tapie, gambler by nature, simply doubled down.

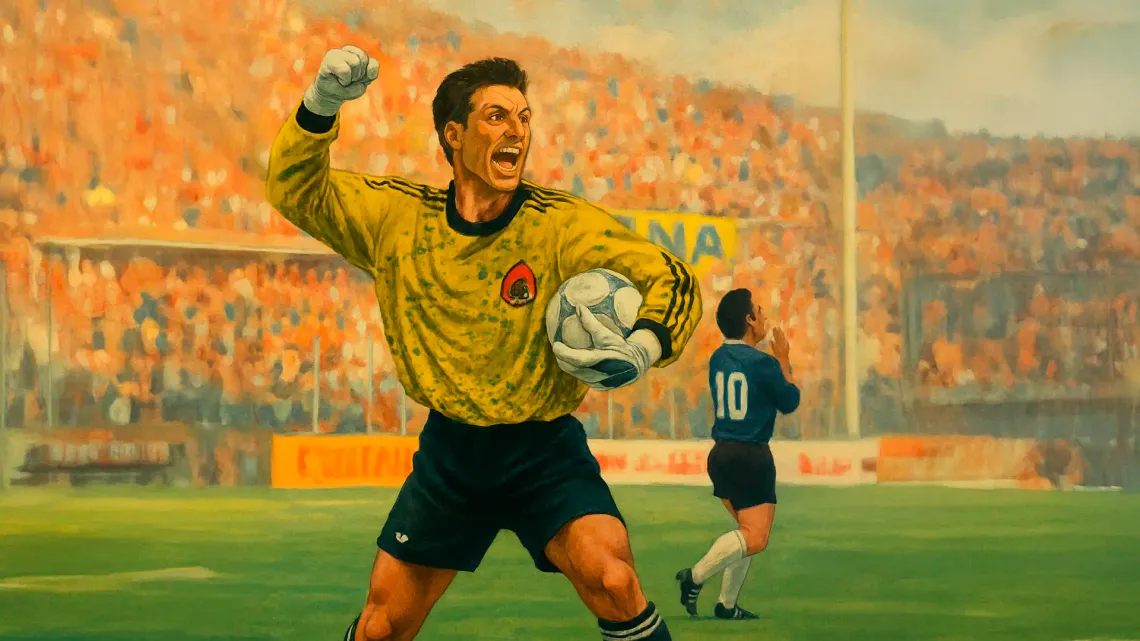

Then came 26 May 1993, Olympiastadion, Munich. Raymond Goethals versus Fabio Capello. Milan arrived like clockwork: Baresi and Maldini anchoring the defence, Rijkaard and Albertini dictating rhythm, Donadoni and Massaro offering width and movement. But Marseille were all focus, drilled and sharpened.

Fabien Barthez, just 21, showed no nerves. Didier Deschamps dictated traffic like a man twice his age. Marcel Desailly read the game like a novel, always on the right page before the plot unfolded. Rudi Völler, cunning and relentless, disrupted the Milan back line with every dart and elbow. Abedi Pelé, elegant and alert, floated through space with his chin high and his eyes scanning for patterns no one else could see.

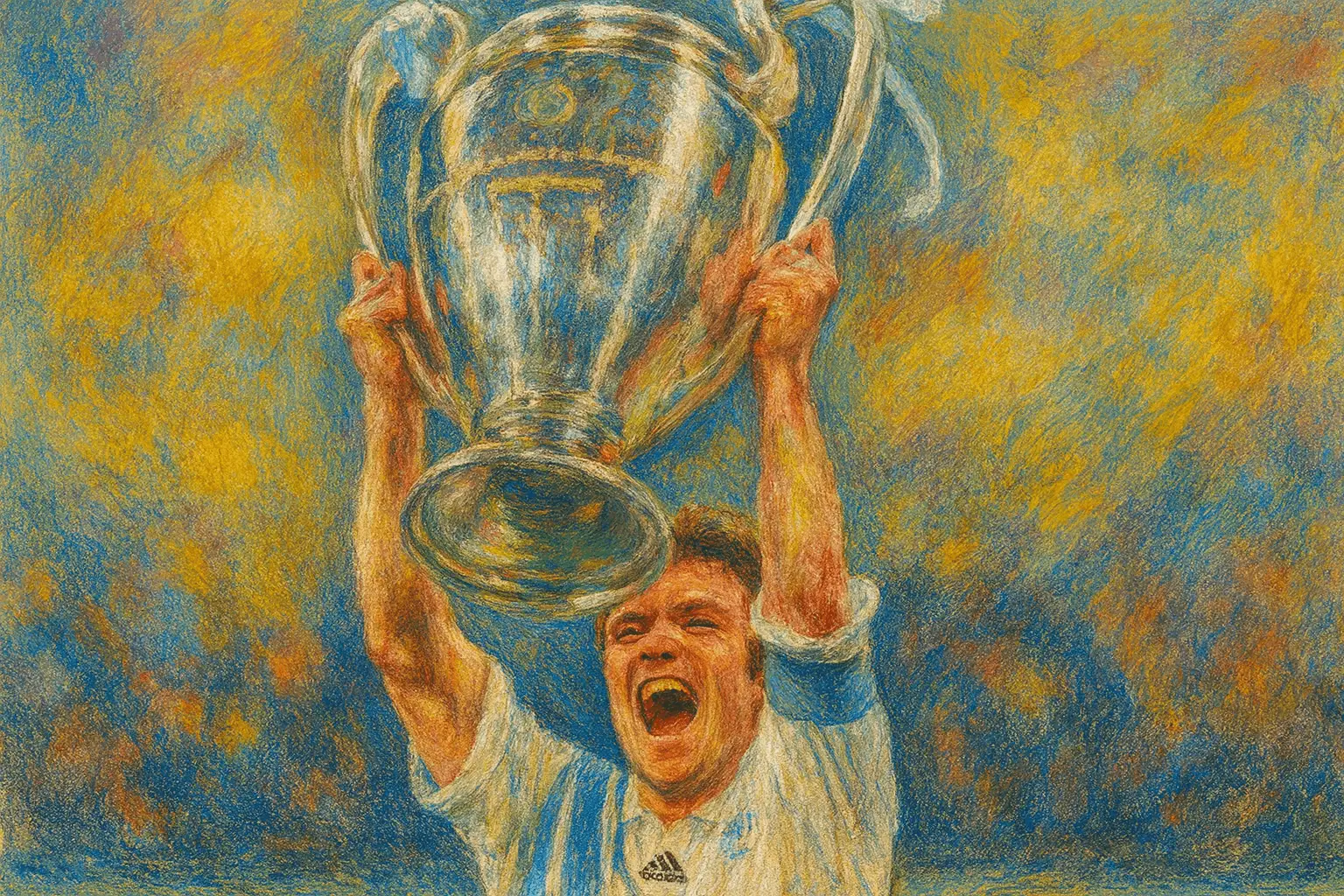

Two minutes before the break, Pelé stepped up to a corner on the right. His delivery curled in towards the near post. Basile Boli, perfectly timed, stormed across his marker and powered a header into the net. 1-0. Just like that.

In the second half, Marseille didn’t retreat - they compressed. They reduced Milan’s options, choked the midfield, and kept their box clear. The Italians were limited to speculative shots and hopeful crosses. No panic. Just control.

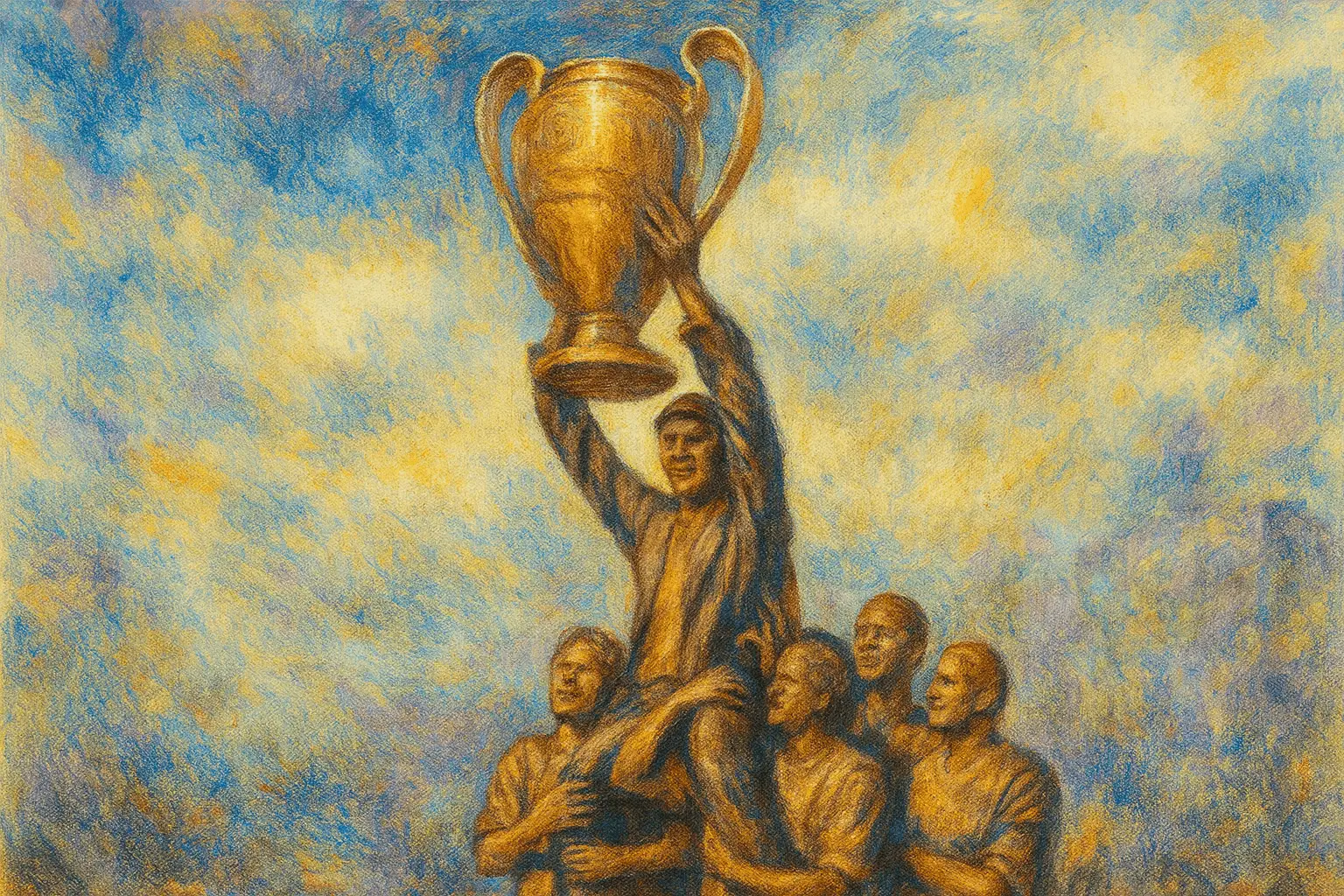

When the final whistle came, Marseille had done it - the first French club to win the European Cup. The Vélodrome’s dreams had travelled across the continent and landed in Bavaria. The city erupted: blue-and-white flags on balconies, open-top buses rolling past the port, chants ricocheting off the hills. Tapie, it was said, ordered via walkie - talkie that Boli remain on the pitch despite injury - a story repeated so often that its truth no longer matters. It fits the myth: the president who coached from the clouds.

For a moment, Marseille was the capital of European football. But under the champagne and the smoke, something darker stirred. Just six days earlier, in Valenciennes, a quiet arrangement had been made. And the fuse had been lit.

Six Days Before Everest

20 May 1993, the Thursday before Munich. Marseille travelled to Valenciennes needing to seal the league title - but more urgently, needing to avoid injuries before facing Milan in the European final. After years of heartbreak, they couldn’t afford another stumble. Everything was on the line.

Behind the scenes, the plan was already in motion. Jean-Jacques Eydelie, a Marseille midfielder with ties to the opposing dressing room, was instructed to make the calls. He phoned Christophe Robert, Jacques Glassmann and Jorge Burruchaga. The message was simple, and cynical: don’t go in hard. Don’t risk hurting us. Just get through the match quietly.

The game ended 1-0 to OM, with Alen Bokšić scoring the only goal. On paper, job done. But one player didn’t stay silent. Glassmann rejected the approach and broke what football rarely allows to be broken - the unspoken code. He spoke out. Investigators followed the trail and soon found US$50,000 buried in the garden of Robert’s in-laws. Eydelie would later confess everything - in a letter written from prison.

The press exploded. The courts followed. Lines were drawn. Marseille’s ultras stood by Tapie, defending their southern emperor. The political and media establishment in the north saw their moment - and moved in for the kill. What began as a backchannel request to “take it easy” became the Affaire VA-OM - the scandal that would unravel a dynasty and drag one of football’s most audacious projects into disgrace.

Collapse and Reckoning

The punishments were brutal. The French Football Federation stripped OM of their 1992-93 league title. UEFA banned the club from defending their Champions League crown in 1993-94, and blocked them from competing in the Super Cup and the Intercontinental Cup. Milan were offered Europe’s place instead. Then, in April 1994, the final blow: relegation to Division 2. The following year, the accounts caved in - over 700 million francs in debt, bankruptcy declared, and a recruitment ban imposed. The road back took until 1996-97.

And yet, one trophy survived. The Champions League title remained untouched. UEFA drew the line at domestic corruption, not European competition. The star stitched above the badge stayed in place - forever celebrated, forever questioned.

For Tapie, the reckoning went far beyond football.

His time at Adidas had once defined the scale of his ambition - a businessman stepping into global industry, not just French football. But by 1993, the shine had dulled. The financial strain was growing, the political climate had shifted, and Tapie’s public image - once his greatest asset - had become a magnet for pressure. With the walls closing in, he was forced to sell.

The buyer? Crédit Lyonnais, the state-owned bank that had helped him acquire it in the first place. The terms were murky, the structure complex, and Tapie always claimed betrayal - believing the bank had manoeuvred behind his back, reselling the company to hidden buyers. Control eventually landed with Robert Louis-Dreyfus, who, in a twist loaded with irony, would go on to buy Olympique de Marseille in 1996, just as the club re-emerged from its lowest point. Tapie lost his company. Then his club. And soon after, his freedom.

He had also been a politician - Minister for the City in the early ’90s - and that made him a bigger target. He lost his parliamentary immunity, was tried for corruption and witness tampering, and in 1997 served eight months in prison. He was barred from public office for five years. Even some prosecutors later admitted the sentence felt sharpened by politics.

But in Marseille, the judgment was different. The south doesn’t forget those who make it dream. The courts may have turned the page, but the streets didn’t. For many, Tapie remained what he had always been: the outsider who had adopted the city, made it believe, and paid the price for daring too much.

He was a businessman, a showman, a builder - and, in the eyes of Marseille, a man who gave everything and lost almost as much. A legend with cracks. The kind football remembers forever.

Scattered Stars

With Marseille forcibly relegated to the second division, the constellation of stars Tapie had assembled broke apart. One by one, they scattered across the European football galaxy - many drawn to Serie A, unquestionably the strongest league of that era.

Didier Deschamps joined Juventus, where he would win everything: Serie A, the Champions League, and eventually, the World Cup with France.

Alen Bokšić, lethal and elegant, signed for Lazio, the club where he’d spend the bulk of his prime.

Angloma went to Torino, while Paulo Futre, always hounded by injuries, took a quieter path to Reggiana.

Marcel Desailly, already gone by mid-season, found glory at AC Milan, winning the Champions League again in 1994 - making him one of the few to win it in consecutive years with different clubs.

Monaco were major beneficiaries of the collapse. They signed Eric Di Meco, and made permanent the move of Sonny Anderson, who had arrived on loan from Servette. Two seasons later, Anderson would be off to Barcelona.

Even Fabien Barthez, the only major star to follow OM into Ligue 2, would leave a year later - to guard Monaco’s net and build his legacy.

Rudi Völler, then 34, returned to Germany to play for Bayer Leverkusen.

Basile Boli went north to Rangers, carrying the memory of Munich with him.

Dragan Stojković, his brilliance curtailed by injuries, moved to Nagoya Grampus in Japan to close out his career.

Rui Barros returned to Portugal and rejoined FC Porto, where he’d first made his name.

OM themselves would need time to rise again. The club didn’t win another French title until 2009-10 - almost two decades after Munich.

The dynasty had crumbled. But its fragments lit up other skies.

The Hand That Gives, The Hand That Takes

Bernard Tapie died in 2021. What remains of him?

He is legend wrapped in contradiction. In Marseille, he’s remembered as the president who gave them Europe and cost them France - the outsider who became theirs. In Paris, and inside the walls of the federation, he’s a cautionary tale: proof that money and politics can infect the soul of the game.

Internationally, that OM side sits on a rare shelf. They modernised French football, set a new bar for ambition, and forced the sport to confront corruption head-on. Tapie’s rise and fall blurred the lines between club and country, between football and finance. He turned a team into a symbol - then watched it collapse under the weight of its own myth.

In Marseille, his name still echoes. At the port. In the stands. On old shirts and young lips. The ghost lingers because the emotions he stirred - pride, defiance, joy - never truly left. Tapie didn’t just run a football club; he gave a city the sense that it could shake the world.

I began this story with the Hand of Vata - a forearm, a goal, a dream denied. Three years later, in Valenciennes, another hand passed an envelope. One kept Marseille out of a final. The other made them the face of scandal.

If you’re looking for justice in football, you’ll rarely find it. But football - and perhaps life - has a way of writing endings with cruel symmetry.

The hand that gives is the hand that takes away.

Subscribe to our newsletter and get our news in your inbox

Member discussion